The New Zealand Underwater Association’s (NZUA’s) Annual report is out with lots of stunning photos from Experiencing Marine Reserves. I do a lot of diving but I’m not a member of NZUA. One of the reasons for this is the associations close relationship with the blood sport organisations (New Zealand Sports Fishing Council / Legasea and The NZ Spearfishing Association).

Environmental campaigns are one of its three pillars but the organisations moral compass is compromised by support for activities that kill our native wildlife. They have been more political recently (lobbying government on fishing policy) but they aren’t developing their own views, just kowtowing to Legasea.

On page 26 of the Annual Report they have said they will be consulting on new Marine Protection Areas (MPAs) and that they support them, but they give some uninformed caveats.

We don’t support MPAs where:

1) An area is not of ecologically significant (This is the exact wording, not a typo from me)

This is an illogical statement because we need to protect a network of representative habitats from fishing. In Aotearoa / New Zealand less than a one percent of our marine environment is protected from fishing, so nearly any protected areas will become ecologically significant.

2) Where removing an area concentrates fishing effort elsewhere

All place based fishing protection displaces fishing effort, including those that limit commercial fishing. It’s a short term loss that is offset by the long term benefits of having an area with larger breeding animals which produce exponentially more offspring. For example it takes thirty six 30cm Tāmure / Snapper to make the same amount of eggs as one 70cm fish (Willis et. al., 2003). And of course the spillover effect which I should not have to explain.

Most divers and the New Zealand public understand this, which is why marine reserves are so popular. There is 77% support for 30% marine protection in the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park and 93% of the submissions for a recent marine reserve proposal for Waiheke Island were supportive, despite opposition from the blood sport lobby groups.

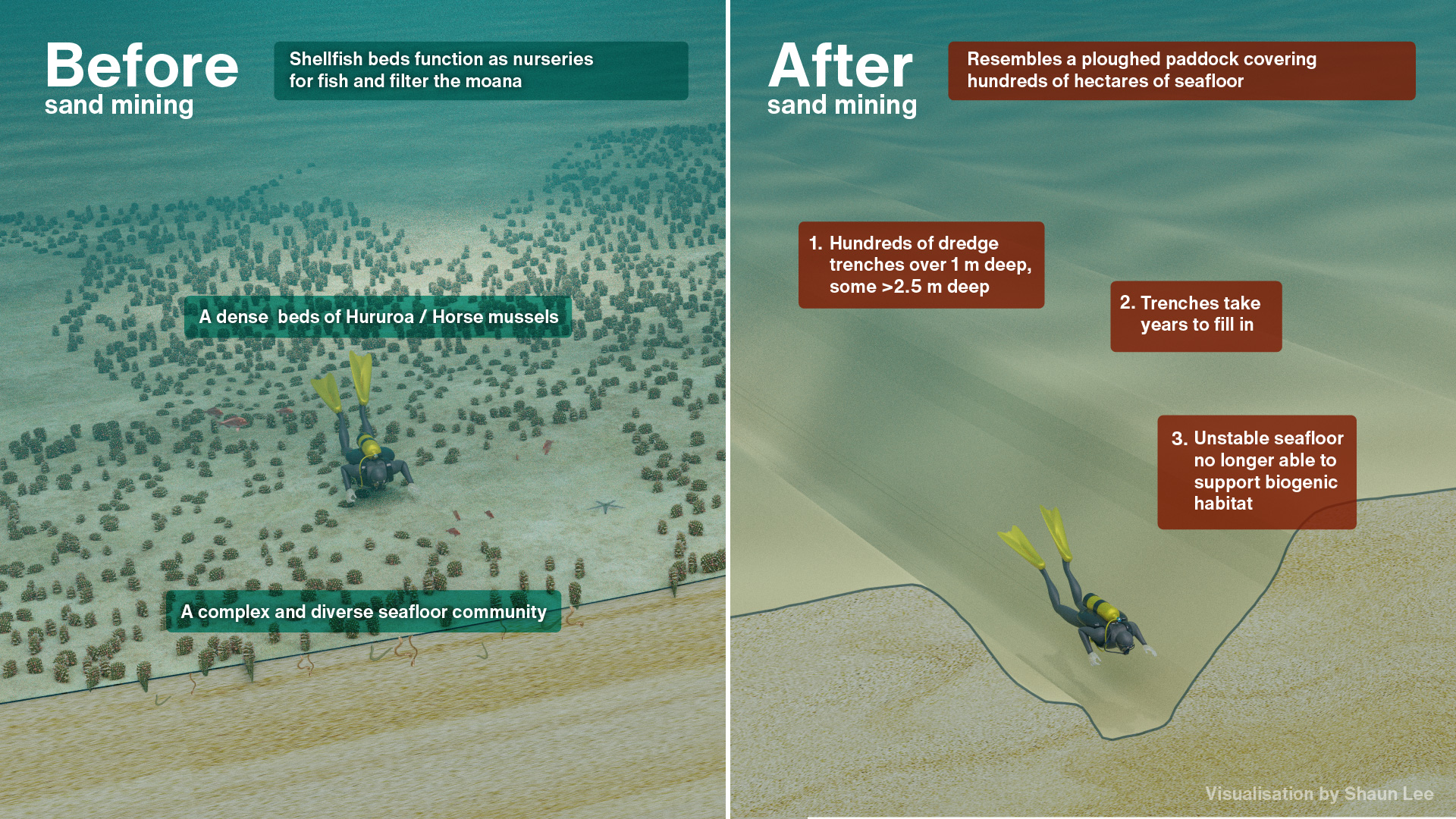

Despite our Marine Reserves being the best places to dive, NZUA say that ‘instead’ they will now support Special Marine Areas (SMAs). They then confuse the term as used in Revitalising the Gulf: Government action on the Sea Change Plan and tell readers that SMA’s include the mussel beds that I have been helping to make (which are not protected from human harvest), seaweed reestablishment and crayfish re-introduction. However these are all examples of active restoration – which I am a big fan of – but it’s really hard, small scale and expensive. Active restoration has its own work stream in the plan and is completely different to SMAs. In the Sea Change – Tai Timu Tai Pari marine spatial plan SMAs are Special Management Areas, they are described as “limiting all commercial fishing, and in addition the restrictions would extend to most recreational fishing (with the exception allowing for ‘low volume/high value’ catch)” They were proposed for the Mokohinau and Alderman Islands. Without strong limits on recreational fishing I expect the SMAs would have failed to create conservation outcomes in a similar fashion to Mimiwhangata. The experts have redesigned them as High Protection Areas (HPAs). The experts decided the SMAs (like Rāhui expressed as section 186 closures) are fisheries management tools rather than conservation tools. It will be interesting to see if DOC can get them to meet the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN’s) high protections standards. Assuming these are the SMAs NZUA refer to, the SMAs would not have meet their own criteria (as an MPA that they are willing to support) because they would have displaced fishing effort.

By using the wrong terminology and examples, we can see NZUA have not paid much attention to the statements. The uninformed caveats for MPAs they would support show a general lack of awareness of ocean conservation. I hope they clarify their position. It sounds like NZUA and the blood sport groups will oppose the HPAs proposed in Revitalising the Gulf. This is disappointing, without more support NZ will stay in the 1% protection level along with Russia and China. See how marine protection in Aotearoa / New Zealand stands on the international stage in this awesome graphic by NZ Geographic.

NZUA are falling out of step with the New Zealand public and drifting away from their international counterparts who are strong ocean advocates. Divers have a unique view of the underwater world, I believe it comes with a responsibility to take care of it. I wish NZUA were more like PADI who are working to protect 30% of our oceans. SSI are also active in Aotearoa / New Zealand with a no harm Marine Conservation programme.

I hope NZUA one day learn to take the same precautionary care for the health of our oceans that they advocate for in diver safety.