Marine restoration is a lazy business. All you have to do is stop fishing an area and marine ecosystems heal themselves. However this is not the case with green-lipped mussels in New Zealand.

100’s of square kilometres of sub-tidal mussel beds were fished to extinction in each harbour around New Zealand.

The industry collapsed and more than half a century later they have not returned. In the Hauraki Gulf there are a few places you can still find Green-lipped mussels. You would think that these places would be deep under the ocean (Green-lipped mussels have been found at 50m deep), but they are not.

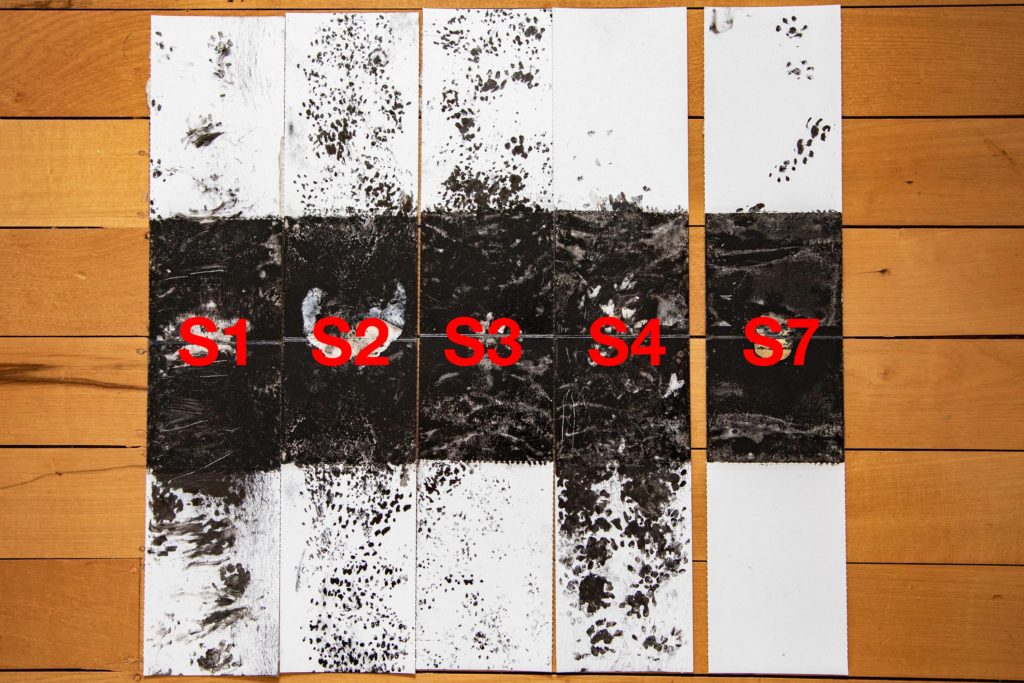

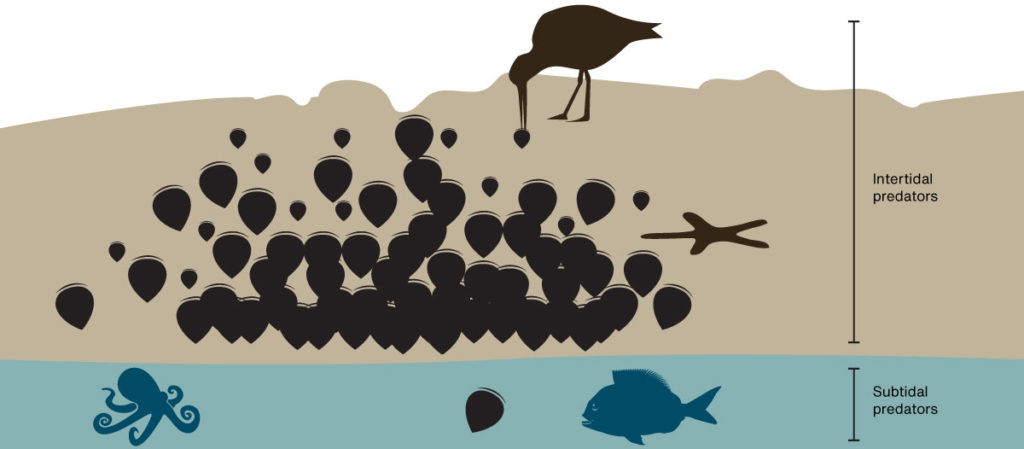

Most are in the intertidal zone on rocky shores. Here there is usually a gradient with mussels thin higher up and getting thicker towards the low tide mark where the abruptly stop. I have asked several local experts and no one has a solid answer why they stop so abruptly.

As we spend 100’s of thousands of dollars restoring sub-tidal beds maybe the key to unlocking a lazier (and cheaper) solution is staring us in the face. Here are some thoughts on why the line exists:

- Avian predation. Every exposed mussel bed has at least one pair of Variable oystercatcher eating the smaller mussels every low tide. So living in the subtidal zone would be of some advantage but we are more likely to see juveniles higher up. This suggests there is even more predation from below.

- Starfish predation. Eleven-armed star fish were a big problem in the first beds put down by Revive our Gulf. However starfish do okay in the intertidal zone and are not particularly abundant in intertidal beds. We don’t see lots of them waiting below the low tide mark next to intertidal mussel reefs.

- Fish predation. This seems like the most obvious cause but surely it can’t be Snapper as they have been fished down to 20% of their natural biomass. Rays are a possibility but I thought I would see more of them in the shallows if this was the case. This southern study looked at predation and found it to be largely subtidal and nocturnal, by fish and large crabs.

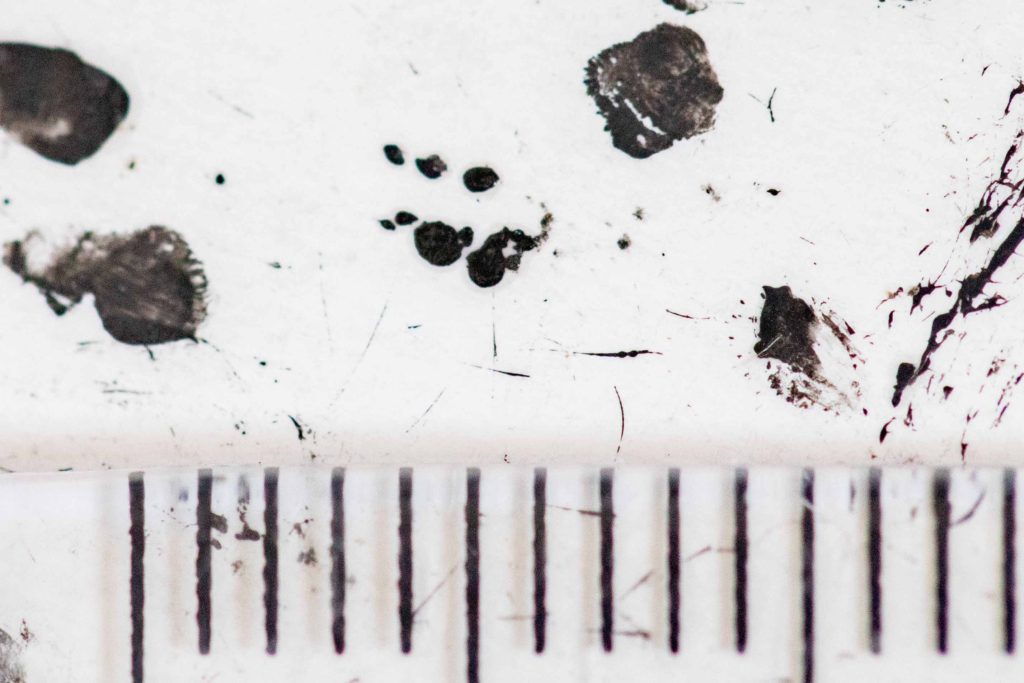

- Octopus predation. They are nearly invisible and love eating mussels so at first this is a good fit. But octopus leave the shells, I will look for evidence on the next intertidal bed I explore. None of the predation theories show why the line is so strong.

- Food. Mussels eat phytoplankton and algae. I am sure there will be more of this close to the surface. I am pretty sure this is why mussel farmers grow their mussels high in the water column. Wild mussels might also benefit from wave action on the rocks as it would increase the oxygen in the water. However I would have thought that these benefits would be offset by the fact they can’t feed while they are exposed to the air.

- Sediment. If there is some other benefit to being exposed to the air maybe it’s that the water in the Gulf just has too much stuff in it. Mussels have to work hard sorting out the food from the dirt, maybe mussels are not good at taking a break and being forced to is good for them. Comparing the condition of intertidal and sub-tidal mussels would help dismiss this idea.

Or maybe like a lot of things in biology it’s a mixture of the above factors. As we are slowly losing our intertidal mussel beds it might be wise to set up a long-term monitoring project that might solve this mystery and inspire lazier restoration methods.