This baseline study helped galvanise Council and Community around the issue and has gone surprisingly well.

It would be good to follow it up later in the year to see if the behaviour changes stick.

Mostly just stuff I am doing to help the planet

This baseline study helped galvanise Council and Community around the issue and has gone surprisingly well.

It would be good to follow it up later in the year to see if the behaviour changes stick.

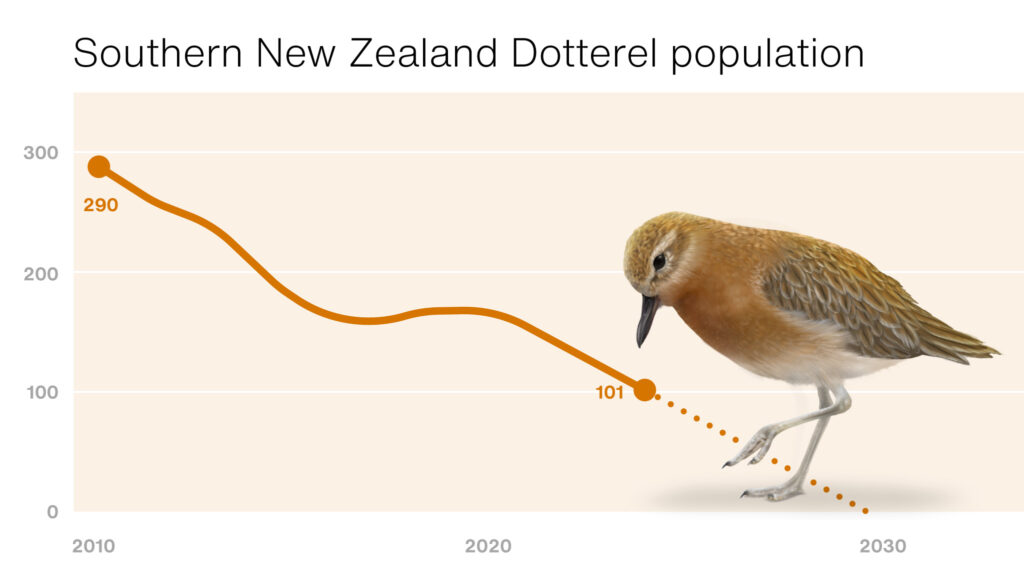

For the past few years, I’ve been supporting the campaign to raise awareness of the critically endangered Pukunui / Southern New Zealand Dotterel, and to see it recognised as New Zealand’s Bird of the Year. Unfortunately, the species is in a dire state and is on track for extinction within the next decade without urgent action.

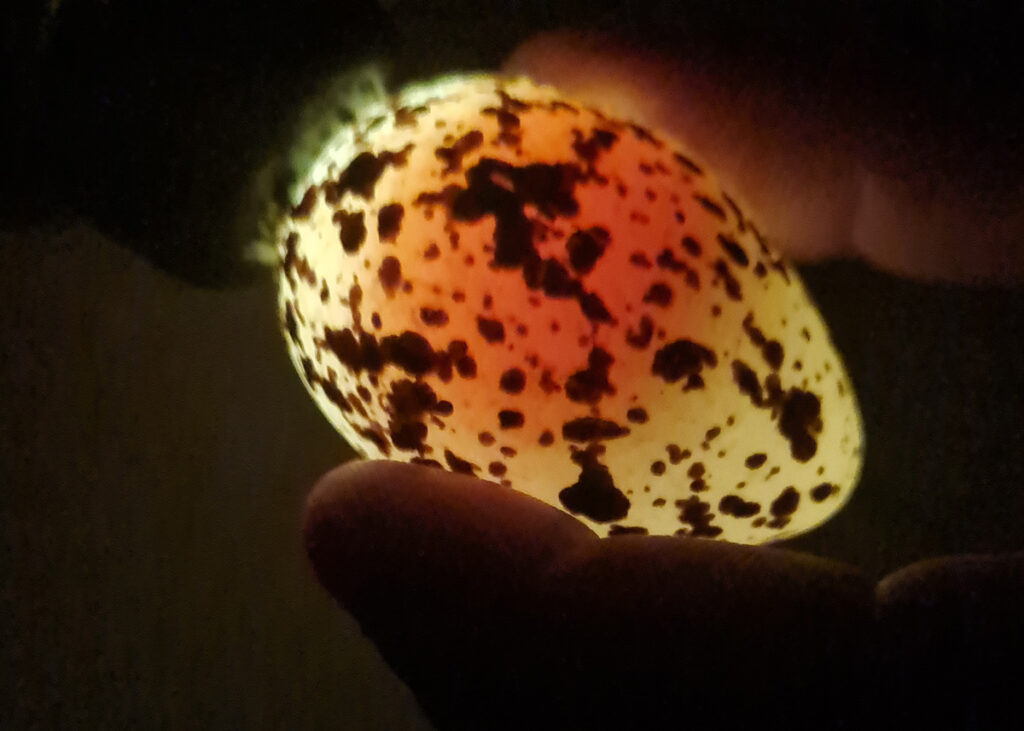

Wanting to contribute in a meaningful way, I offered to produce decoy Pukunui eggs that the Department of Conservation (DOC) rangers could use to distract predators (primarily feral cats). However, DOC staff explained that decoy eggs would be most valuable during fertility checks, providing a substitute to keep adult birds settled on the nest while real eggs were removed for assessment. With only 12 nests found during the 2023/24 breeding season, it’s essential that each actively managed nest is as productive as possible. Ensuring birds aren’t incubating infertile eggs reduces wasted effort and limits their exposure to predators. Candling is only carried out when a bird has been sitting longer than the expected incubation period, suggesting the egg may not be viable.

Using publicly available data on NZBirdsOnline, I 3D printed a set of six replica eggs, carefully matching the size, shape, and weight of real Pukunui eggs. Each egg was then airbrushed and speckled with acrylic paint to resemble the real thing as closely as possible. I also created custom protective cases for each egg to ensure they could be transported safely to Rakiura and carried in rangers’ backpacks during fieldwork.

According to the rangers, the decoy eggs have been effective in keeping the birds settled during fertility checks, giving staff the time they need to carry out this crucial work without disrupting the breeding process.

I’m proud to have volunteered my time to support the recovery of this remarkable species. You can help too by donating to the New Zealand Nature Fund.

My speech to commissioners in the Waikato Regional Coastal Plan hearing on including fishing controls. There was some mention of tubeworm mounds beforehand so I also gave the commissioners an off-the-cuff intro to these ones which was appreciated.

Change in commercial landings in Waikato CMA 2005 to the most recent fishing year

I’m so grateful to Ben Goodwin & Amanda Choy who helped me collate the Threatened and At Risk species of the Tāmaki Estuary for the Tāmaki Estuary Protection Society.

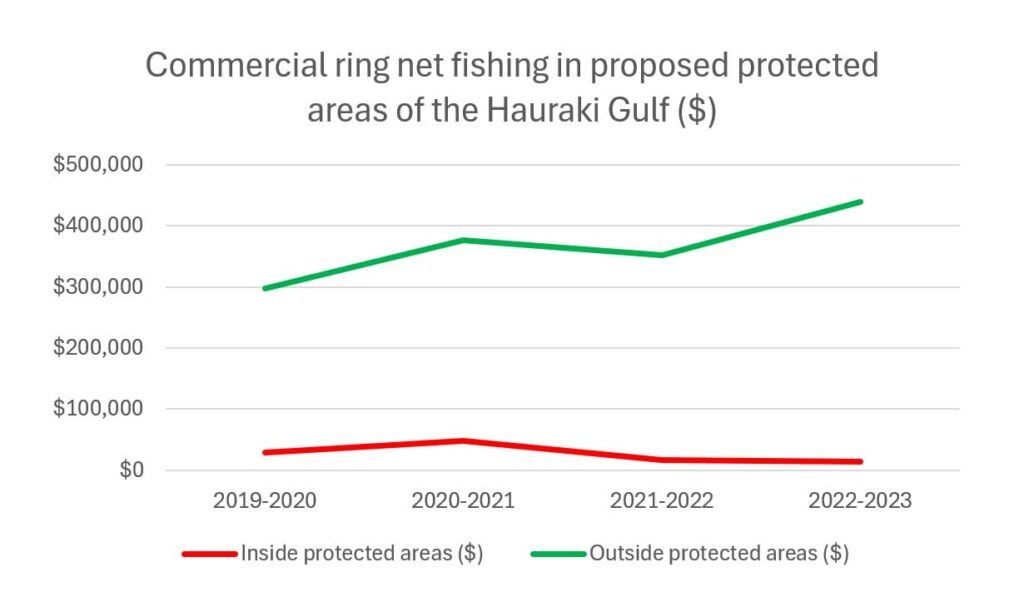

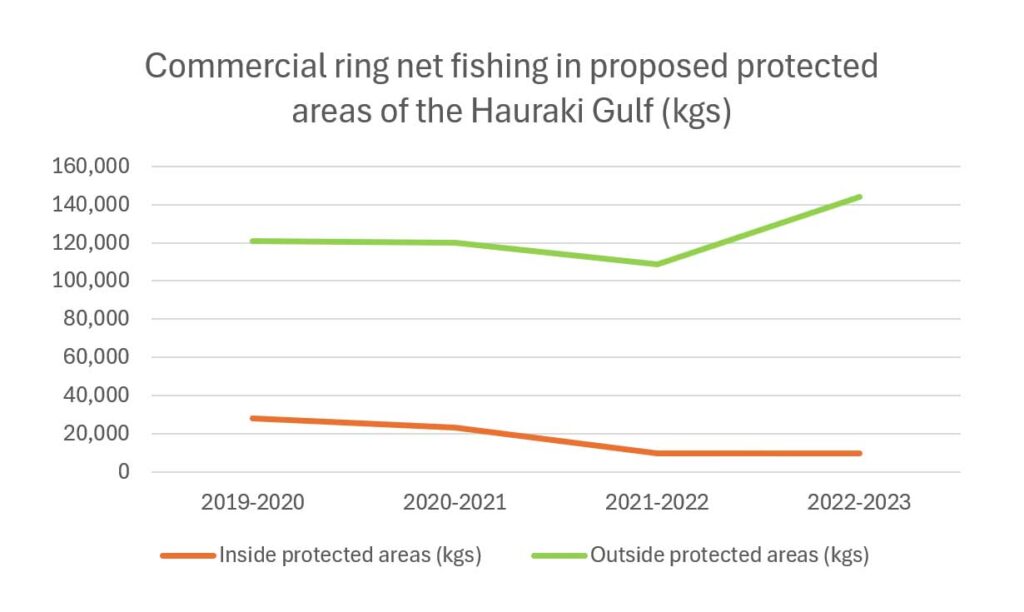

After a decade of consultation and compromise on the Hauraki Gulf / Tīkapa Moana Marine Protection Bill the government is proposing last minute changes to allow commercial ring net fishing in two areas. I have provided ministers analysis showing the proposal would compromise the objectives of the marine protection areas. I also asked Fisheries New Zealand for data on ring net fishing. They replied 49 working days later with a partial response, two days after the bill was debated in the house and I had complained to the Ombudsman.

The data provides factual information to support new arguments against the proposal to allow commercial ring net fishing in the proposed protection areas.

| 2019-2020 | 2020-2021 | 2021-2022 | 2022-2023 | Average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inside protected areas (kgs) | 28,051 | 23,125 | 9,575 | 9,713 | 17,616 |

| Outside protected areas (kgs) | 120,961 | 119,841 | 108,851 | 143,954 | 123,402 |

| Inside protected areas ($) | $28,383 | $47,838 | $16,280 | $13,852 | $26,588 |

| Outside protected areas ($) | $297,053 | $376,722 | $352,221 | $438,854 | $366,213 |

Recreational fishing lobbyists LegaSea are making a last ditch effort to stop the Hauraki Gulf / Tīkapa Moana Marine Protection Bill. Here are ten reasons why Scott Simpson and other MP’s should support the bill as it stands:

I have asked Fisheries New Zealand for information regarding the proposed concession to allow commercial ring net fishing in two of the High Protection Areas in the Hauraki Gulf / Tīkapa Moana Marine Protection Bill. My understanding is that Ministers may need to debate the concession in the House before the information is available. So I have sent them an early impact analysis.

I asked Maritime NZ for the oil spill trajectory modelling from the wreck of the RMS Niagara. I have uploaded it here for anyone interested.

My layman’s notes below:

MNZ have kindly tried to explain it to me, but I don’t really understand why the 2016 modelling was only done with about 97 tonnes of oil (100 m³) when the Rena leaked 350 tonnes. The RMS Niagara could store more than 4,000 tonnes of oil and experts have estimated that there could be 1,400 tonnes remaining. This means the estimated volume of oil on individual beaches and the length of shoreline impacted could be dramatically worse.

The probability of oil contact with the shoreline increases by 10% if it happens in summer (This is tara iti / New Zealand fairy tern breeding season, we are down to nine breeding female left, note the Rena spill killed 2,000 birds). The impacts move a bit further south in winter.

It’s interesting to see the areas impacted. The spill expands outward from the wreck largely as you would expect, but there are interesting details. For example, it will be twice as bad at Goat Island than further up the coast at Mangawhai. If it’s going to be visible at the Mokohinau Islands in just a few hours, I think it might be a good idea to install a webcam there.

Harbours and bays are less impacted, but I wonder if this is an artefact of the modelling software. It definitely shows that even a 97-tonne spill will span a massive length of our coastline. For example, Waikato Regional Council also needs to be prepared.

I’d like a better understanding of the risk and the mentioned contingency plan. It would be helpful to run scenarios with different response times, gear, and methods; this may have already been done.

UPDATE: 10 Dec 2024. I asked Maritime NZ for costings for Stage 2 of the survey of the RMS Niagara wreck. Summary: The estimated cost for Stage 2 of the RMS Niagara wreck survey totals NZ$13.74 million, split into two parts. Part 1 involves a visual survey using a remotely operated vehicle (NZ$1.3 million). Part 2, requiring a dynamic positioning vessel due to proximity to submarine cables, includes hull cleaning, oil level measurement, and risk assessment (NZ$12.44 million). A moored vessel alternative for Part 2 costs NZ$4.5 million but is not recommended due to the risk to undersea cables. An additional NZ$500,000 is estimated for oil pollution response readiness during the survey.

There is some confusion about the change in these numbers because of the way the data was reported. I made this graphic to also clear up that as of April 2024 there is no data that has been made public from the on-board cameras for commercial fishing vessels programme.

Data sources: Overview of the rollout of on-board cameras on commercial fishing vessels February 2024 Update at 1 April 2024: Progress on the rollout