The New Zealand government has just introduced ‘fast track’ legislation to bypass the usual checks and balances for environmental protection. This means less voice for nature in the application and approval process. To help address that gap, I’ve been looking into the impact a proposed sand mine might have on the tipa / scallop population in Bream Bay. I shared the report with quota owners who have been fishing the area, they agreed with my findings and have sent the report to Ministers.

Ring net fishing in proposed protected areas

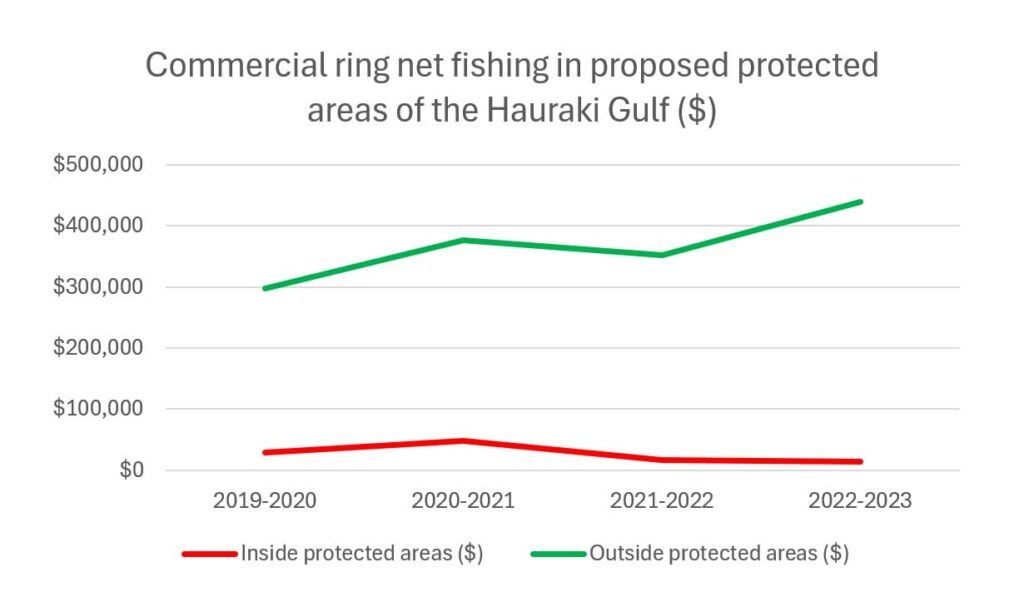

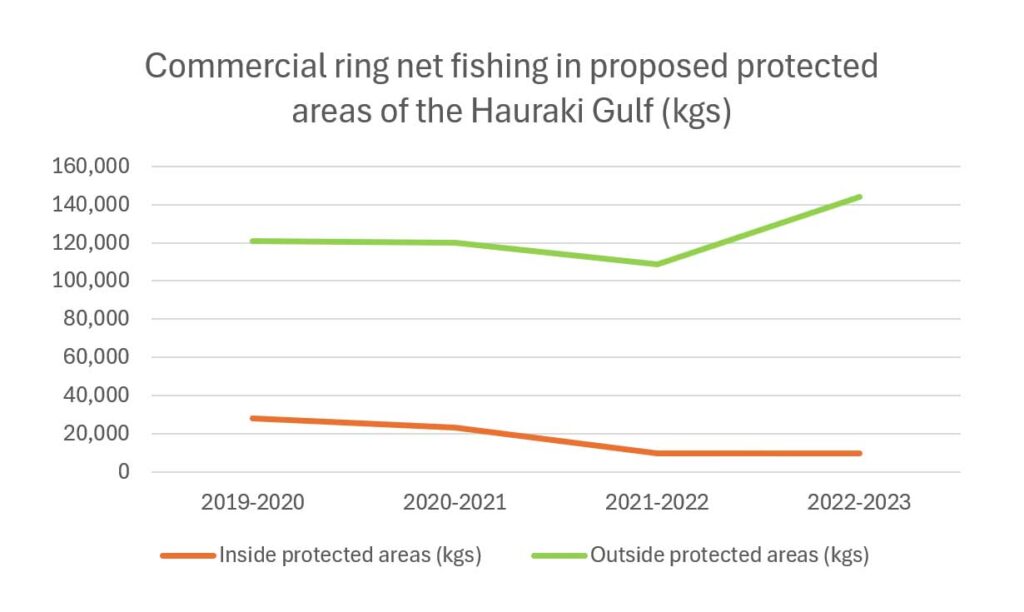

After a decade of consultation and compromise on the Hauraki Gulf / Tīkapa Moana Marine Protection Bill the government is proposing last minute changes to allow commercial ring net fishing in two areas. I have provided ministers analysis showing the proposal would compromise the objectives of the marine protection areas. I also asked Fisheries New Zealand for data on ring net fishing. They replied 49 working days later with a partial response, two days after the bill was debated in the house and I had complained to the Ombudsman.

The data provides factual information to support new arguments against the proposal to allow commercial ring net fishing in the proposed protection areas.

- Commercial ring net fishers in the Hauraki Gulf catch an average of $26,588 worth of fish in the proposed protected areas, which is only 6.8% of their total Gulf catch (averaging $366,213 annually). In weight, this equates to 17,616 kg or 12.5% of their total catch. This demonstrates that the proposed protected areas account for a small percentage of their overall income, especially considering these fishers also operate on Auckland’s west coast.

- The average annual catch from the proposed protected areas is 17,616 kg worth $26,588, which is small compared to the natural variability in catch outside these areas. For example, the catch outside protected areas fluctuates by 35,103 kg and $141,801 across years, far exceeding the potential loss from protection.

| 2019-2020 | 2020-2021 | 2021-2022 | 2022-2023 | Average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inside protected areas (kgs) | 28,051 | 23,125 | 9,575 | 9,713 | 17,616 |

| Outside protected areas (kgs) | 120,961 | 119,841 | 108,851 | 143,954 | 123,402 |

| Inside protected areas ($) | $28,383 | $47,838 | $16,280 | $13,852 | $26,588 |

| Outside protected areas ($) | $297,053 | $376,722 | $352,221 | $438,854 | $366,213 |

Close CRA 2

I am publishing my draft submission on CRA 2 early. Key points below:

- The ecological imbalance caused by overfishing kōura (spiny rock lobster) in CRA 2 has led to the proliferation of kina barrens, devastating kelp forests along Northland’s east coast.

- Kelp forests in the Hauraki Gulf could be worth up to USD 147,100 per hectare annually, far exceeding the $10.17 million export value of CRA 2. Kina barrens, by contrast, provide no ecological or economic value.

- Fisheries New Zealand’s reliance on biased data, such as Catch Per Unit Effort (CPUE), underestimates kōura depletion. Independent research shows kōura populations, even in marine reserves, are well below natural levels.

- The proposal to close commercial and recreational kōura fishing in the inner Gulf for 10 years is the largest fisheries closure ever suggested for the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park. However, fisheries independent data shows it’s not enough.

- A new biomass target is precedent-setting and a significant step for Ecosystem-Based Management initiated by Sea Change – Tai Timu Tai Pari. A 3x BR target is essential to control kina populations, halt the spread of kina barrens, and restore productive kelp forests.

- Independent data must be prioritised, and a precautionary approach adopted, including a full closure of the CRA 2 fishery. Further delays will only worsen environmental and economic losses.

Ten reasons why MPs should support Gulf protection bill

Recreational fishing lobbyists LegaSea are making a last ditch effort to stop the Hauraki Gulf / Tīkapa Moana Marine Protection Bill. Here are ten reasons why Scott Simpson and other MP’s should support the bill as it stands:

- Broad Public Support for Protection: There is overwhelming public support for marine protection. The bill will increase protection from 0.3% to 6%. 77% of the public want much more (30%) of the Gulf protected.

- eNGO Support for Increased Protection: Environmental groups have consistently asked for more protection than the bill currently provides, indicating that the bill is already a compromise aimed at balancing diverse interests.

- Protection to Address Depletion and Habitat Damage: The bill addresses overfishing, habitat destruction, and declines in marine biodiversity in small areas. Lage scale bottom-impact fishing is being delt with through a different process.

- Scientific Evidence Supports High Protection Areas (HPAs): While recreational fishers claim there is no evidence to support HPAs, scientific studies worldwide demonstrate that protected areas are fantastic for restoring fish populations and biodiversity.

- Minimal Economic Impact on Recreational Fishing: Recreational fishers will still have access to 87.4% of the Gulf for fishing. The HPAs cover a small portion, reducing the impact on fishing activities while promoting long-term marine ecosystem health.

- Displacement Concerns Are Overstated: The limited fishing restrictions introduced by the bill are offset by gains in fish abundance in nearby areas, as larger, reproductively mature fish spill over into fished zones, ultimately benefiting fish stocks outside HPAs.

- Limited and Controlled Commercial Fishing: The bill may include ring-net fishing in two HPAs compromising their objectives. However, 10 high protection areas and the two marine reserve extensions will be unaffected by the amendment.

- Ecosystem Benefits for Seabirds and Marine Species: High Protection Areas will help protect seabird foraging grounds and marine ecosystems, which directly impacts terrestrial food webs and biodiversity on islands in the Gulf.

- Strong Legislative Foundations: The bill aligns with New Zealand’s marine protection obligations under international agreements, reflecting a responsible approach to safeguarding marine biodiversity while considering local cultural and socio-economic factors.

- A Balanced Approach to Sustainable Use: This bill offers a compromise between no-fishing reserves and managed-use areas, establishing a multi-use marine park with regions for both recreational fishing and high protection. This approach meets both conservation and fishing community interests without entirely prohibiting either.

Open letter to ministers debating the Gulf protection bill

I have asked Fisheries New Zealand for information regarding the proposed concession to allow commercial ring net fishing in two of the High Protection Areas in the Hauraki Gulf / Tīkapa Moana Marine Protection Bill. My understanding is that Ministers may need to debate the concession in the House before the information is available. So I have sent them an early impact analysis.

Brief for restoring extremely degraded seafloor ecosystems

I don’t know how to solve this problem, so I am writing it up as a public brief for people smarter than me.

Brief for restoring extremely degraded seafloor ecosystems

Soft sediment marine ecosystems support diverse and productive biogenic habitats like shellfish beds, sponge gardens, tubeworm fields, and bryozoan mounds. Direct impacts such as mobile bottom contact fishing, and indirect impacts such as sediment pollution, reduce the function of these habitats. Stopping or reducing the impacting activities can help the habitats recover naturally over many decades. Active restoration (like mussel and oyster seeding) can be done in areas where the habitat is not recovering naturally; however, some environments can be too degraded for these methods.

Problem

In my opinion, at least tens of square kilometres of the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park are too degraded to restore with known techniques. In these extremely degraded areas, the seafloor is very soft, deep mud. It’s not lifeless; there are burrows and infauna present. But the areas would be more diverse and productive if the seafloor was less soft with less sediment in suspension. Even when pollution input has been reduced in these extremely degraded areas, legacy sediment is constantly resuspended – choking filter-feeding animals and smothering photosynthesising plants. It is difficult to visually convey the condition of these ecosystems, as visibility is usually less than 30 cm on a good day.

Solutions

To increase biodiversity in these areas, the benthic enhancement method must be low-cost at scale. This means traditional erect concrete and steel structures are not likely to be the solution. In my opinion, resurfacing the seafloor with demolition rubble or quarried aggregate is too extreme because it kills all the infauna. Anything heavy deployed will immediately sink into the mud, anything lighter than the mud will quickly be covered by sediment. A smarter solution might contain one of these elements:

- Local pits or trenches to collect the most mobile sediment.

- Dispersed erect artificial shellfish (think horse mussels) to slow benthic currents and allow sediment to fall out of the water column in fields or fences.

- Regular deployments of waterlogged woody debris.

- Biological concrete structures that grow using elements from the local environment.

- Hardened local seafloor sediments (think mudbrick or mudcrete).

- Growing dense algae at the surface which will 1) slow currents and surge to reduce resuspension 2) drop fragments for sequestration, feeding invertebrates, collecting sediment and seafloor hardening.

Caution

While these solutions will restore some ecosystem function they will not restore the original ecosystems. Hard surfaces will likely be first colonised by invasive species and the new habitat will offer more ecosystem services but be novel / new. We must first halt the destructive activities that degraded the seafloor ecosystems.

Artificial Reef or Fish Aggregation Device?

Artificial reefs have significant potential to boost fish populations, even surpassing pre-fished levels or what is possible in marine reserves. However they have a checkered history overseas, with many reefs:

- Failing to restore native biodiversity to levels of those of conserved natural reefs (Bracho-Villavicencio et al. 2023).

- Creating hard surfaces which are favoured by invasive species (these species often travel to new areas on hard structures) (Gauff et al. 2023).

- Created as a convenient way to dispose of something which pollutes the marine environment (E.g. UnderwaterTimes.com 2006). They can also attract polluting activities (Zhang et al. 2019).

When considering building an artificial reef, it is crucial to determine whether it will provide additional habitat to support reef communities or merely function as a Fish Aggregation Device (FAD). Like artificial reefs, FADs are man-made structures which are attract fish to a specific area by providing habitat and shelter for marine life. The problem with FADs is that they decrease local fish populations by concentrating them in one area where they are easily targeted by fishers (Cabral et al. 2014) as illustrated below.

To define the size of the habitat required to avoid FAD functionality, you could base it on the home range of each fish species you want to increase. For example:

The most studied fish in the Hauraki Gulf is the tāmure / snapper, which show high site fidelity to reef habitats. Tāmure in deep soft sediment habitats are quite mobile, with a median distance of 19 km, and some movements up to 400 km. In contrast tāmure in shallow rocky reef habitats have restricted movements, with a median distance of 0.7 km (Parsons et al. 2011). You can see this in small marine reserves with shallow rock reefs, such as the 5 km² Cape Rodney – Okakari Point Marine Reserve (Goat Island), which effectively increase the size and abundance of this species. Additionally, tāmure around mussel farms have been found to be healthier than those in surrounding soft sediment habitats (Underwood 2023). The studied mussel farms were near rocky reefs and covered about eight hectares (200 x 400m).

This means fished artificial reefs should be deployed at hectare scales to avoid acting as population sinks. For tāmure, an area about the size of eight rugby fields is a considerable undertaking, but to avoid your reef functioning as a FAD for fishing, it is essential to spread your structure over a large area. If this sounds more like ‘habitat enhancement’ than an artificial reef, then perhaps that is a better way to frame your design. Of course, this consideration is unnecessary if your artificial reef is not fished.

REFERNCES

Bracho-Villavicencio et al., 2023 https://doi.org/10.3390/environments10070121 A Review of the State of the Art and a Meta-Analysis of Its Effectiveness for the Restoration of Marine Ecosystems. Environments.

Cabral et al., 2014 https://academic.oup.com/icesjms/article/71/7/1750/664488 Modelling the impacts of fish aggregating devices (FADs) and fish enhancing devices (FEDs) and their implications for managing small-scale fishery

Gauff et al., 2023 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2023.151882

Unexpected biotic homogenization masks the effect of a pollution gradient on local variability of community structure in a marine urban environment.

Parsons et al., 2003 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/225304000_Snapper_Pagrus_auratus_Sparidae_home_range_dynamics_Acoustic_tagging_studies_in_a_marine_reserve Snapper Pagrus auratus (Sparidae) home range dynamics: Acoustic tagging studies in a marine reserve

UnderwaterTimes.com 2006

https://web.archive.org/web/20170912095117/https://www.underwatertimes.com/news.php?article_id=36210951740 Two Million Tire Artificial Reef to be Removed Off Florida Coast; Smothering Corals

Underwood et al., 2023 https://www.aquaculturescience.org/content/dam/tnc/nature/en/documents/aquaculture/AquacultureHabitatComparativeReport.pdf Habitat value of green-lipped mussel farms for fish in northern Aotearoa New Zealand

Zhang et al., 2019 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134768

Microplastic pollution in water, sediment, and fish from artificial reefs around the Ma’an Archipelago, Shengsi, China.

Inconclusive evidence of the cause of kina barren formation?

In an article titled “Shane Jones sets sights on killer kina – An industrial grade problem” the Fisheries Minister Shane Jones is quoted as saying “Some ecologists say it’s related to overfishing but the evidence is not conclusive in that regard. From my perspective as Fisheries Minister, I can provide some practical tools through the law, to allow local communities to go and cull them.”

The consultation document on the proposed tool provides a definition of kina barrens and clearly explains they are formed by a “low abundance of predator species“.

I was concerned that our Fisheries Minister could be so poorly informed so I asked Fisheries New Zealand for:

- Any recent New Zealand research findings that corroborate the Minister’s statement that the cause of kina barens is inconclusive.

- Any ministerial advice provided to the Minister that supports his statement about the formation of kina barrens.

Fisheries New Zealand replied in detail today with recent information that has been provided to the Minister with respect to kina and kina barrens (note I have run the scanned pages through a text recognition software).

Fisheries New Zealand have clearly supplied conclusive evidence that kina barrens are related to overfishing. They have not supplied any research findings that corroborate the Minister’s statement that the cause of kina barens is inconclusive. I don’t know where Shane Jones is getting his alternative facts.

Of interest (and to his credit) Shane Jones has asked staff to increase the pace on starting pre-engagement to identify voluntary and/or regulatory measures to support increased large rock lobster abundance in areas with kina barrens (p25, detail on p21). Progress on this workstream seems to have been withheld and its clearly delayed as the other (extractive) measures mentioned have been consulted on. Two new measures that staff have suggested include a Maximum Legal Size Limit for Lobster and ‘Catch Spreading’.

While we wait for government action, millions of kina relentlessly devour our kelp forests.

The unmanaged fisheries of the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park

In New Zealand, we have 75 fish populations that are supposed to be managed sustainably. The main way we do this is by setting limits on how many fish can be caught, known as the Total Allowable Catch (TAC). We don’t keep regular track of the fish caught by recreational and cultural fishers. The only annual numbers are for commercial fishing, which has a limit called the Total Allowable Commercial Catch (TACC).

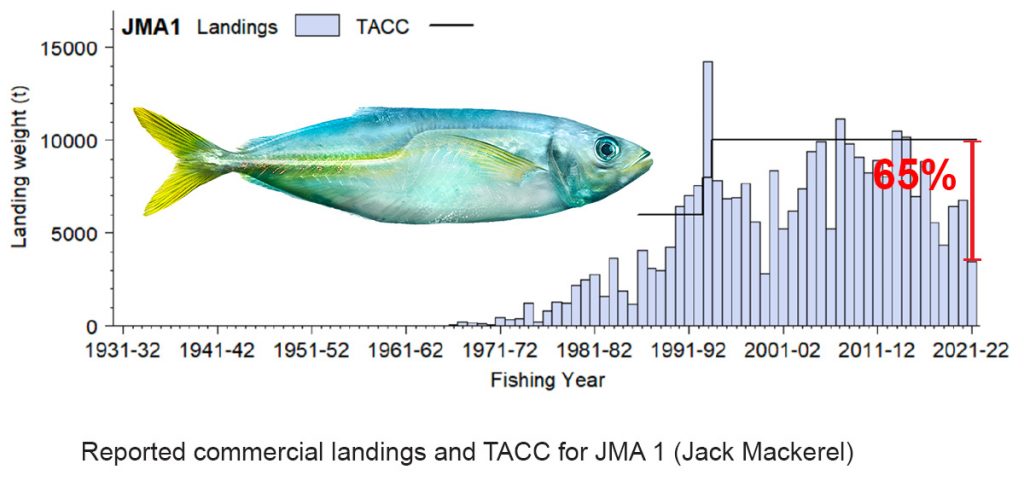

What’s puzzling is that for many fish populations, the TACC is set way higher than what’s actually being caught, and it’s been like that for years without any change. To me, this means these fish aren’t really being managed at all. Of the 75 in Aotearoa there are 16 fish populations in the Gulf that stand out as ‘unmanaged’ due to their TACC being significantly higher than the actual catches.

I had high hopes for the new Fisheries Management Plan for the Gulf, thinking it might sort out these unmanaged populations. I tried to get some answers by writing to the minister, and when that didn’t work, I filed an Official Information Act request. The reply came from Simon Lawrence at Fisheries New Zealand, but it wasn’t what I hoped for. They’re only planning to review four out of the 16 unmanaged populations this year – Flatfish, Rig, Blue cod, and Red cod. That leaves Pipi, Horse mussel, Paddle crab, Anchovy, Sprat, Pilchard, Jack mackerel, Pōrae, Leatherjacket, Trumpeter, Longfin eel and Spiny dogfish unmanaged. Four of these fish are at the bottom of the food web and are critical for the Gulf ecosystem function. Horse mussels are endemic (found only in New Zealand) and aggregations dense enough to be called beds are now extinct in the Gulf, Longfin eel are also endemic and going extinct.

So here we are, with a fisheries plan that talks a big game about moving towards an ‘ecosystem-based fisheries management‘ approach, but we’re not even effectively managing individual fish populations.

LegaSea’s displacement argument

LegaSea are asking their supporters to object to the Hauraki Gulf Marine Protection Bill due to concern’s about displacement.

“We do not believe the proposed protection measures go far enough to restore fish abundance and biodiversity in the Hauraki Gulf. Marine protection and fisheries management controls need to go hand-in-hand, otherwise all we will do is shift current fishing effort into our neighbour’s waters. We want 100% of the Hauraki Gulf seafloor protected from destructive, mobile fishing methods including bottom trawling, Danish seining and dredging. And, we want Ahu Moana, a joint iwi/hapū and community driven solution to resolve local depletion issues.” (Full email published here).

If we forget about the many non-fishing benefits of marine protection, then also forget about the fisheries benefits of marine protection (nursery and spillover) then forget about the fisheries plan which aims to rebuild stocks including Ahua Moana we are left with LegSea’s naïve argument over a limited amount of fish. Does it stand up?

No, the recreational losses for all species fished in the HPAs total 293 tonnes, the proposed commercial reductions from the corridors will total between 632-1017 tonnes.

Update January 2024. Marine scientists at the University of Auckland have done some excellent work looking at the displacement argument.

Math + references:

Calculating the weight of recreational catch lost to HPAs

Recreational fishers harvested 2,068 tonnes of snapper from the HGMP in 2017/18 fishing year. 9.58% of the recreational fishing effort is in the proposed High Protection Areas. The HPAs will reduce recreational fisheries catch of snapper by 198 tonnes.

Recreational fishers harvested 517 tonnes of kahawai from the HGMP in 2017/18 fishing year. 9.58% of the recreational fishing effort is in the proposed High Protection Areas. The HPAs will reduce recreational fisheries catch of kahawai by 50 tonnes.

These two species represent 82% of the fish (by weight) caught in the Gulf in the 2017/18 fishing year.

– https://gulfjournal.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/State-of-our-Gulf-2020.pdf

Recreational catch in the HPAs for the 2017/18 fishing year = 248 + 18% (45) = 293 tonnes.

Calculating the weight of commercial catch lost to trawl corridors

Option 1 would result in an estimated reduction in landings of approximately 632 tonnes of fish per year. Option 4 would result in an estimated reduction in landings of approximately 1017 tonnes of fish per year.