My report to the Hauraki Gulf Form on Kekeno / NZ Fur Seal Mortalities for 2021.

Presented on the 28th of February 2022.

Mostly just stuff I am doing to help the planet

My report to the Hauraki Gulf Form on Kekeno / NZ Fur Seal Mortalities for 2021.

Presented on the 28th of February 2022.

Here is my submission on the Hākaimangō – Matiatia Marine Reserve (Northwest Waiheke Island) application. Details and submission form here. Feel free to use any or all of this submission yourself and send it to: waihekeproposal@publicvoice.co.nz

There have been decades of korero about marine protection in the Hauraki Gulf / Tīkapa Moana / Te Moananui-ā-Toi. Everyone knows we urgently need more protection but the Governments proposals are too small, experimental, slow and ignore Waiheke Island.

The only concern I have about the Hākaimangō – Matiatia Marine Reserve (Northwest Waiheke Island) application is the lack of published support from iwi authorities. My understanding is that the applicants and the Department of Conservation continue to engage iwi (nine months to date), but while iwi authorities at this stage have not committed their support they are interested in dialogue and importantly they have not opposed the application. Two leading descendants of 19th century Waiheke Ngāti Paoa chiefs, Moana Clarke and Denny Thompson have expressed open support. Iwi politics in the Treaty settlement era are complex and difficult for me as a pakeha to understand. I am concerned about the considerable expectations put on Māori. If we limit our support to co-designed or iwi led marine reserve applications we would be burdening iwi with a responsibility for marine heath they do not seem to be resourced to implement. There are no published concerns about the proposal from iwi. 77% of Māori support 30% marine protection in the Gulf (Hauraki Gulf Forum Poll 2021). I hope that the iwi leaders will put the mauri / lifeforce of the HGMP first and support the application. In the meantime the cautious approach of iwi authorities is no reason not to support the application. If any iwi do have concerns we should take great care to hear and work through those concerns, they have significant rights as mana moana.

UPDATE 28 February. A local iwi body the Ngāti Paoa Trust Board are supporting the application.

1. We don’t have enough protection. A tiny 0.33% of the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park (HGMP) is fully protected from fishing, the governments Revitalising the Gulf plan will hopefully increase this area to 0.575% by late 2024 (Revitalising the Gulf 2021). The other forms of protection suggested in the plan all involve some kind of fishing. We need places where with intact ecosystems where our taonga and heritage don’t get eaten. The proposed Hākaimangō – Matiatia Marine Reserve is a significant addition at 0.195% of the HGMP. All the proposed protections need to be actioned as soon as possible to reverse the decline of biodiversity and abundance in the HGMP (State of our Gulf 2020). If all the proposals are accepted only 6.7% of the HGMP will be protected from fishing (excluding cable zones which are not designed to protect biodiversity). We will need many more proposals to meet the Hauraki Gulf Forums goal of 30% protected.

2. It’s long term. Rāhui enacted through section 186 of the Fisheries Act only last for two years. This is not the right tool to use to sustain large breeding animals live for more than 50years. Tāmure / Snapper can live to at least 60 years of age (Parsons et. al. 2014).

3. It’s big. For decades scientists have been telling us that our marine reserves are not big enough to protect wildlife from the edge effect. If approved at 2,350 ha Hākaimangō – Matiatia would be the largest marine reserve in the HGMP.

4. It’s in a great spot. The site covers an ecological transition zone between the waters of the inner and outer Gulf. The inner Gulf is slightly cooler, more turbid, shallower, low energy (sheltered by a screen of islands including Waiheke Island) compared to the outer Gulf which is deeper, warmer, clearer and comparatively high energy marine environment. The site was select by marine biologist Dr Tim Haggitt after doing extensive surveys around Waiheke Island in 2015. The area is geologically remarkable for its extensive underwater platforms and terraces, the diversity in physical habitat is reflected in the flora and fauna.

5. There are plants and animals left worth protecting. Functionally extinct species like Kōura / Crayfish (Jasus edwardsii & Jasus verreauxi) are still found in the area so the recovery time here will be faster than other overfished areas of the HGMP.

6. We need more baby fish. It takes thirty six 30cm Tāmure / Snapper to make the same amount of eggs as one 70cm fish (Willis et. al., 2003). This marine reserve would dramatically increase egg production in the HGMP. Marine reserves make a disproportionate (2,330% Tāmure / Snapper in the reserve at Leigh) larvae spillover. Adult Tāmure / Snapper within the reserve at Leigh were estimated to contribute 10.6% of newly settled juveniles to the surrounding 400km2 area, with no decreasing trend up to 40km away (State of our Gulf 2020).

7. Fishing on the boundary will be awesome. The proposed marine reserve is big enough for people to fish the borders with a clear conscience. Fishing here will be popular with many big fish leaving the area (See Halpern et. al. 2009 on spillover).

8. People want marine reserves. Marine reserve support is strong and getting stronger. On island support for marine protected areas from island residents was 67% with off-island ratepayers at 54% in 2015. A 2021 poll by the Hauraki Gulf Forum shows general support for 30% protection at 77% with only 5% opposition. The poll showed no difference in support from Māori.

9. It’s a great cultural fit. Most people who live on Waiheke Island really care about the environment. Conservation values are strong across the different local communities.

10. It will be great for education. The marine reserve will create much richer outdoor education opportunities for the young and old people of Waiheke and Auckland. Rangitahi in particular will benefit from being able to experience an intact marine ecosystem. Te Matuku Marine Reserve is less suitable for education because the water clarity is dramatically impacted by sediment.

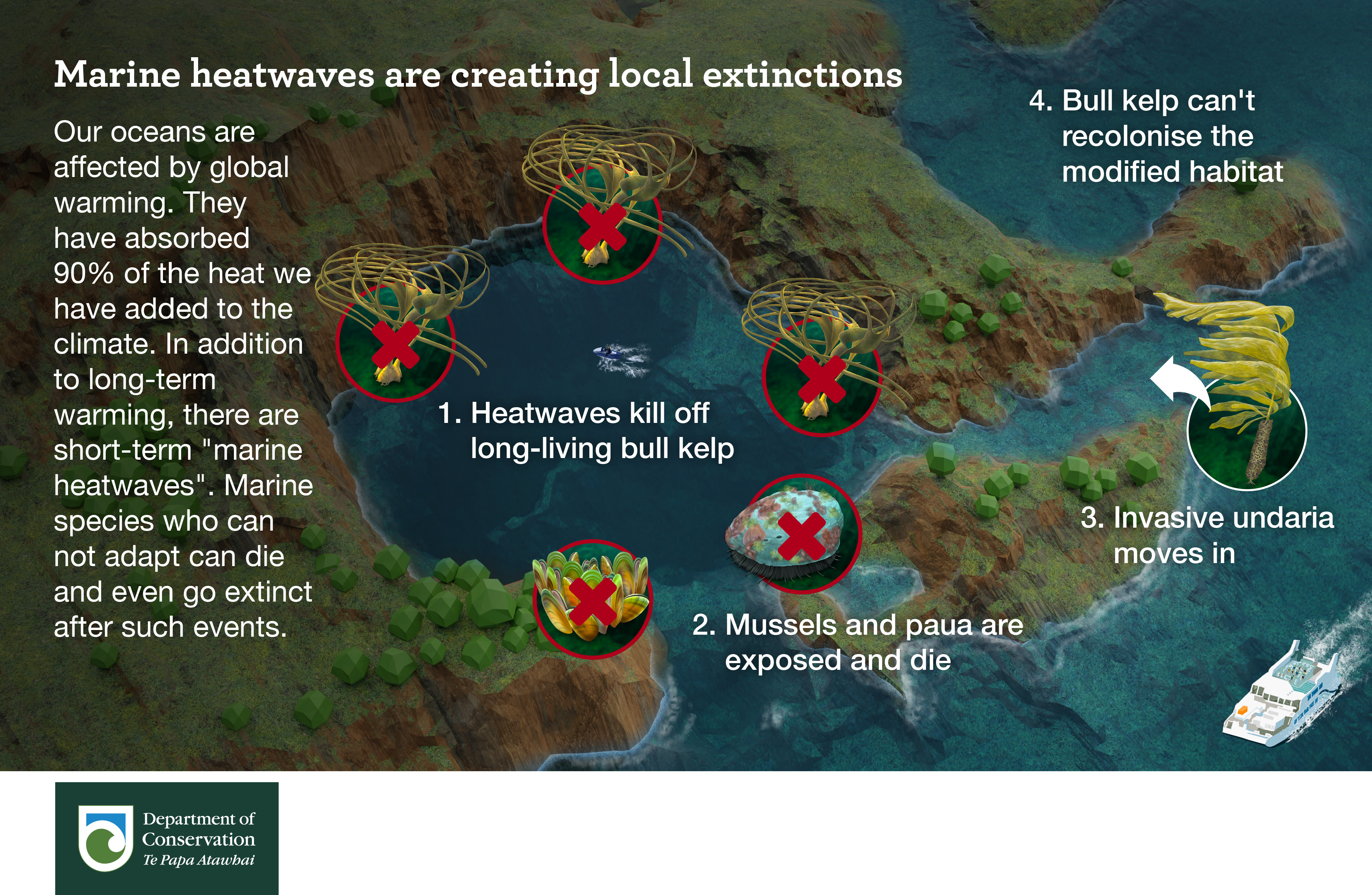

11. Resilience to climate change. By maximising biodiversity and abundance the marine reserve will protect the HGMP from climate change impacts, particularly heatwaves, invasive species and ocean acidification. Marine reserves are like insurance against uncertainty.

12. Improving the economy via commercial fisheries. Juvenile Tāmure / Snapper leaving the Cape Rodney to Okakari Point (Goat Island/Leigh) Marine Reserve boosted the commercial fishery by $NZ 1.49 million per annum (Qu et. al. 2021). Auckland University found 10.6% of juvenile snapper found throughout the Gulf – up to 55 km away were sourced from from this one marine reserve. The researchers found economic benefits to the recreational fishery are even more substantial. There are other commercially fished species in the area The proposed marine reserve is four times bigger than the Goat Island reserve.

13. A benchmark. No harm marine reserves provide a reference point for assessing the impacts of our activities elsewhere. “As kaitiaki in the broadest sense, we have an obligation to preserve natural examples of marine ecosystems” – State of our Gulf 2020. Data obtained from marine reserve monitoring compliments fisheries information and matauranga Māori to help us understand environmental change.

14. Science. Marine reserves are a natural laboratory. They have contributed massively to our understanding of marine ecology and ecological processes. Many of our leading marine scientist studied and conducted research in marine reserves at Leigh, Tāwharanui, Hahei and elsewhere. Of course the Marine Reserves Act expressly recognises the scientific importance of marine reserves. Scientific research is an over-riding priority in the Act,

15. Tourism benefits. The marine reserve will add to the growing ecotourism opportunities on Waiheke Island. It complements the $10.9 million dollar investment in Predator Free Waiheke (Predator Free 2050 Limited 2021) which has a vision to become the world’s largest predator-free urban island. The marine reserve will be much cheaper to create and maintain and will deliver a mountains to the sea nature experience.

16. Return on investment. The Cape Rodney to Okakari Point Marine Reserve (Goat Island) generated $18.6 million for the local economy in 2008 at a cost of about $70,000 for the Department of Conservation (State of our Gulf 2020).

The Hauraki Gulf / Tīkapa Moana / Te Moananui-ā-Toi can not afford to have this application sit on a shelf waiting for stronger political leaders. Please start the process of creating the Hākaimangō – Matiatia Marine Reserve and healing the wider area as soon as possible.

Hākaimangō – Matiatia Marine Reserve (Northwest Waiheke Island) https://friendsofhaurakigulf.nz/

Hauraki Gulf Forum Poll 2021. https://gulfjournal.org.nz/2021/11/results-of-hauraki-gulf-poll/

Parsons DM, Sim-Smith CJ, Cryer M, Francis MP, Hartill B, Jones EG, Port A Le, Lowe M, McKenzie J, Morrison M, Paul LJ, Radford C, Ross PM, Spong KT, Trnski T, Usmar N, Walsh C & Zeldis J. (2014). Snapper (Chrysophrys auratus): a review of life history and key vulnerabilities in New Zealand, New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research, 48:2, 256-283, https://doi.org/10.1080/00288330.2014.892013

Predator Free 2050 Limited 2021. Annual Report 2021 https://pf2050.co.nz/predator-free-2050-limited/

Revitalising the Gulf 2021 https://www.doc.govt.nz/our-work/sea-change-hauraki-gulf-marine-spatial-plan/

State of our Gulf 2020 https://gulfjournal.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/State-of-our-Gulf-2020.pdf

Qu et. al. (2021). Zoe Qu, Simon Thrush, Darren Parsons, Nicolas Lewis. Economic valuation of the snapper recruitment effect from a well-established temperate no-take marine reserve on adjacent fisheries. Marine Policy. Volume 134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104792

Willis, T.J., Millar, R.B. and Babcock, R.C. (2003), Protection of exploited fish in temperate regions: high density and biomass of snapper Pagrus auratus (Sparidae) in northern New Zealand marine reserves. Journal of Applied Ecology, 40: 214-227. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2664.2003.00775.x

Halpern, B., Lester, S., & Kellner, J. (2009). Spillover from marine reserves and the replenishment of fished stocks. Environmental Conservation, 36(4), 268-276. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892910000032

Fisheries New Zealand (FNZ) is designing an NZ first Fisheries Management Plan for the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park that they are calling Ecosystem Based as part of the Revitalising the Gulf – Government Action on the Sea Change Plan. They are seeking an advisory group as part of their discourse of delay (Revitalising the Gulf was launched six months ago). I have not asked to be part of the process. Because the advisory group does not have any decision making capability it won’t be very effective in managing commercial fisheries (like Sea Change), this is because FNZ has been captured by industry (Parker 2016). FNZ also only want advice from people with experience in Fisheries Management, based on the state of Gulf this is like asking the Tabacco Industry to regulate smoking. But they might be able to reduce recreational catch which I think has the biggest impact on the Gulfs reef ecosystems. Unfortunately of the five voices, only one will be from the environmental sector, so it doesn’t have much of a chance of being ecosystem based, and to be truly ecosystem based; the scope would have to include the management of other impacts on the ocean like plastics and sediment (Government departments have hand picked recommendations from the Sea Change which was the only attempt at an integrated management plan). The plan will start to address the effects of fishing which FNZ should have been doing since the act was established in 1996. The Sustainable Seas Challenge has a project investigating what Ecosystem Based Fisheries Management would look like for the Gulf, it’s so political even the scientific proposal is two months late.

The outcomes of the proposed plan are:

Like more than 10% of New Zealanders I don’t eat our native wildlife, my suggestion for creating a really Ecosystem Based Fisheries Management Plan would stop all fishing in the Gulf and not be very popular 😀 So here are some ideas that might be a bit more palatable. First of all my outcomes would be different:

Obviously we need to stop bottom contact fishing (as per Sea Change and the Hauraki Gulf Forum goals) but on top of that, this is what I would do to achieve the above outcomes.

These species need to recover to much higher levels to perform ecosystem services and increase biodiversity. Species I consider functionally extinct. Kutai / Green-lipped mussels, Kōura / Spiny rock lobster and Packhorse rock lobster, Hapuku, Sharks etc.. Where populations of species are not known fishing should stop (precautionary approach) and the group complaining about the closure should pay for the science to measure it (user pays). Many species are in such a bad state we now need to also stop fishing practices that might kill them as bycatch (eg. Killing juvenile Hapuku who have a pelagic phase in Purse Sein nets). The sooner we stop killing the species the sooner we will see them recover. The advisory group will suggest long rebuild times for populations so they can keep killing as much as they can for as long as possible. I would stop all killing right now and wait until stocks have recovered to 80% biomass and there contribution to ecosystem function has been measured before considering harvesting again.

This has been said before but just for marine mammals “Management of the Greater Hauraki Gulf should take into account the potential for trophic and system-level effects of re-establishment/recovery of marine mammals towards historical levels.” MacDiarmid 2016. I think it should apply to other functionally extinct predators like Hapuku.

Not everybody will love this idea but everyone will love the result – clearer water. The Gulf has been overloaded by sediment and nutrients and the tap is still running. Filter feeding animals help clear the water by removing sediment from water while looking for food (mostly phytoplankton).

Increasing populations of filter feeders that live on the seafloor, Kutai / Green-lipped mussel, Tipa / Scallop, Tuangi / Cockle, Hururoa / Horse mussel, Tio / Oyster etc will increase water clarity which will increase kelp biomass and carbon sequestration. Other benefits include more complex benthic habitats which are nurseries for fish, removal of harmful pathogens and even the production of sand. Increased water clarity benefits visual predators like Tāmure / Snapper and Human spearfishers.

In some parts of the Gulf a lot of money is being spent trying to actively restore shellfish, by not killing shellfish in areas where we still have remnant populations we can increase larval supply across the Gulf. Passive and active restoration activities are complementary.

By weight most of the fish in the Gulf are also filter feeders. These forage fish swim around in large schools with their mouths open feeding on zooplankton. Unlike the bivalves listed above they do not bind sediment up in balls and deposit it on the seafloor. This means not all the above benefits of increasing their populations apply, however its likely they play a critical role in the Gulfs ability to sequester carbon. I’m most interested in increasing forage fish populations because they are critical to many Gulf food webs. Commercial harvest of some forage fish like Blue mackerel has increased 300% in the last 20 years. This is reducing the amount of food available to protected species that we want more of, like whales and seabirds. Populations of most forage fish are not known so that would be the first step, I would then set the Total Allowable Catch (TAC) for Ecosystem Based Management (EBM) very low (E.g. 20% unfished biomass) and invest more in monitoring the breeding success of their predators (seabirds and cetaceans) and adjust the TAC accordingly.

Restoring Kōura / Spiny rock lobster and Packhorse rock lobster numbers is going to take a long time and they will need help to push back Kina / Sea urchin barrens and regrow our kelp forests. We can fix this by creating a maximum size limit for Tāmure / Snapper. Bigger snapper are better at managing Kina populations and are dramatically better at making baby Tāmure / Snapper. If the later is true for all finfish then it makes sense to introduce the maximum size limit across all species. Recreational fishers could still have fishing competitions but they would have to be catch-and-release. Large fish should learn to avoid hooks overtime reducing harm and selecting for traits that support catch-and-release. R&D would be required to match the gear to fish size for the longline fisheries but as I said earlier this group hasn’t been set up to have the power to influence commercial take.

We need to get much less good at killing fish. Methods like nets, pots and dredges need to be banned along with long lining. Gear restrictions should also apply to methods with high levels of bycatch. This is not just what is used (eg. set nets catching protected bird species) but also how (eg. Let’s stop all fishing in workups and spawning aggregations). This means a lot of re-educating fishers, the introduction of a license would be sensible (like Australia which has had licenses for 20 years and is not known for being progressive on wildlife protection).

Source–sink dynamics are not hard for anyone interested in population management to understand. No-harm areas where populations can reach near 100% of their un-fished state can feed exploited areas. No one would design a conservation management plan on land without a wildlife refuge. I don’t see why the design of network of such areas should not be part of an ecosystem based population management plan in the ocean.

“It would be logical to close some scallop beds and create passive restoration (broodstock areas) to increase the fishery yield”

– Dr Mark Morrison, Shellfish Restoration Co-ordination Group, December 2021.

A recent poll showed that the 30% protection policy had 77% support from the public including Māori. These areas would serve as a reference point to compare the impacts of fishing elsewhere in the Gulf and provide the best possible resilience to climate change impacts like ocean acidification (which scares me more & more every time I look into it). One of the most difficult hurdles for Marine Reserve applications is the perpetual nature of the policy. Creating MPAs under a fisheries management plan would be a lot easier, voices of those seeking protection in the Gulf (like me) will go quiet the longer the areas stay closed to fishing and visa versa.

It’s a good time to share ideas on what an Ecosystem Based Fisheries Management plan would look like. There are some attempts to define it here, but they all try to avoid the idea of simply killing less native wildlife, no one wants to pay for that research.

MacDiarmid 2016. Taking Stock – the changes to New Zealand marine ecosystems since first human settlement: synthesis of major findings, and policy and management implications. New Zealand Aquatic Environment and Biodiversity Report No. 170 A.B. MacDiarmid et al. June 2016. Ministry for Primary Industries.

Parker 2016. Hon David Parker https://www.parliament.nz/en/pb/hansard-debates/ rhr/document/HansS_20160920_054787000/parker- david

UPDATE 6 MAY 2022

The Hauraki Gulf Fisheries Plan Advisory Group has been announced. The Chair is an old school fisheries scientist who is responsible for the current fish populations. There are three commercial voices and one (or one and a half) recreational. There are only two voices for serious change. I am not counting on it delivering significant change.

UPDATE 3 MAR 2023

My submission on the proposed plan which refines thoughts I began in this blog post. It includes additional critique of the draft plan and many new measures.

The tipa /scallop population in the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park (HGMP) is on the verge of collapse due to mismanagement by Fisheries New Zealand (FNZ). The current population is one fifth of what it was in 2012 (when they last surveyed the beds). Huge cuts are needed to save the population, most of us will experience the loss in the supermarket or the boat ramp. Here are the things they did wrong (many by their own admission).

You can read the report that recommends closing the fishery here. I will be supporting a full closure and recommending a discontinuation of the four irresponsible behaviours. I hope that all the tipa beds recover from the closure but it’s likely many of them will not. We have recently seen this in SCA7 Golden Bay, SCA7 Tasman Bay where the FNZ collapsed the fishery, and in three individual beds (Ponui-Wilsons, Shoe-Slipper, Barrier & Kawau) in the SCA CS fishery (HGMP). Enabling the long-term damage of a habitat forming species is not just fisheries collapse or functional extinction – it’s ecocide.

Note this paper recommends eliminating bottom contact fishing is the most effective intervention to rebuild a depleted scallop populations in New Zealand

Although rock pools are a very small part of our ocean they were a big part of my childhood. It’s sad to see them declining and I’m supporting this section 186A closure. I have turned my submission into a PDF you can download, add your name to and email to FMSubmissions@mpi.govt.nz

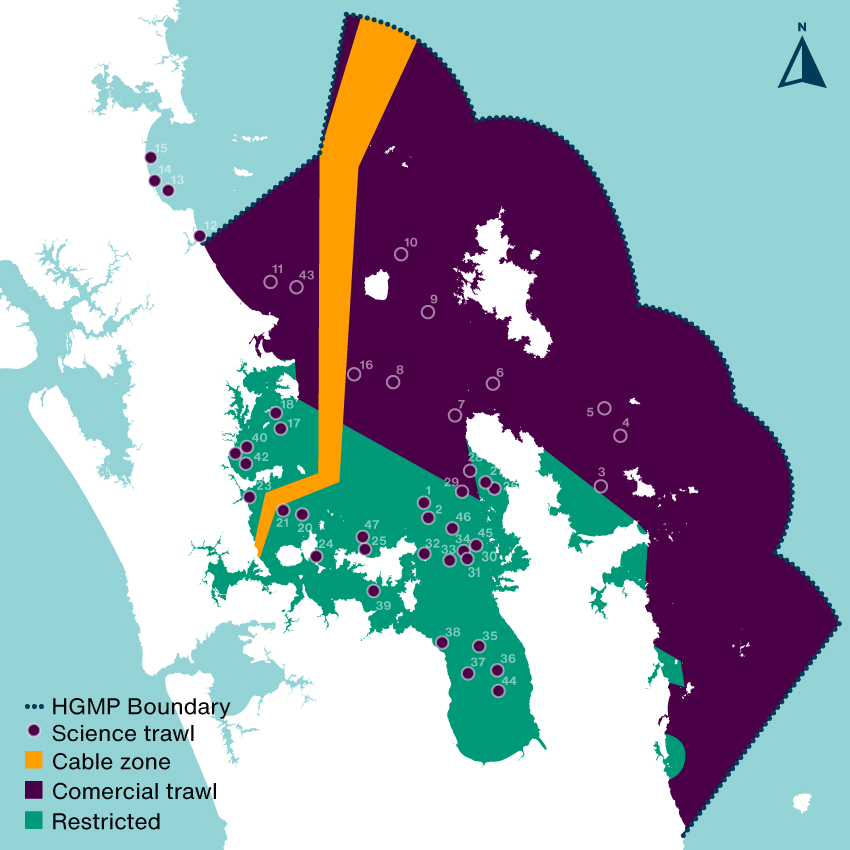

The most barbaric way to answer this question would be to drag a giant net around and count what you kill but you’re not allowed to do that in the inner Gulf where trawling is restricted… unless you have a research permit from Fisheries New Zealand (FNZ). Despite calls to stop bottom trawling in the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park (HGMP) (Sea Change 2017 & Hauraki Gulf Forum 2021) FNZ have started doing these trawls regularly, they justify the trawls are required to gather information on the Tāmure / Snapper population. They haven’t done research trawls like this since the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park Act came into effect in the year 2000 (NIWA 2019). In areas where trawling is restricted (c25% of the HGMP), the study was like bulldozing a regenerating forest to count the birds. A disgraceful act on private land let alone a national park.

The nets are massive, wider than a rugby field. FNZ were just interested in killing demersal fish (goundfish), they dragged theses massive nets along the seafloor smashing down anything that lives there and creating giant sediment plumes that contribute to climate change. In areas that have been closed to trawling for decades there are patches of horse mussel beds, sponge gardens and tubeworm mounds and other habitats regenerating after decades of abuse from heavy machinery. You can read about them in the report (NZFAR 2021) where they are described as ‘foul’ a horrible word which suggests there is something ugly about these beautiful benthic epifauna that are working hard (day and night) to clean up our pollution (they are nearly all filter feeding animals). In defense of FNZ they did try and avoid areas with a lot of immobile sea life but they failed so badly that they had to stop trawling on several occasions, this shows that a) the seafloor is recovering and b) echosound is no good for measuring trawling impact on benthic life.

Although the percent of trawled seafloor was small (less than 1% of the study area) the areas bottom trawled were huge:

| 39 rugby fields between Shakespear Regional Park and Rangitoto Island | Stratum 1386 |

| 54 rugby fields of the inner Firth of Thames | Stratum 1887 |

| 68 rugby fields of the mid Firth of Thames | Stratum 1268 |

| 88 rugby fields in a west-east band North of Waiheke Island | Stratum 2229 |

| 59 rugby fields around the western side of Waiheke Island | Stratum 1149 |

| 41 rugby fields north of Whangaparāoa Peninsula | Stratum 1284 |

| 40 rugby fields northwest Coromandel | Stratum 9292 |

| 60 rugby fields south of the line dividing the inner gulf | Stratum 1219 |

| 59 rugby fields from Bream Bay to Mangawhai | Stratum 1449 |

| 49 rugby fields between Aotea / Great Barrier Island and Ahuahu / Great Mercury Island | Stratum COLV |

| 77 rugby fields north of the line dividing the inner gulf | Stratum LITB |

A total of 615 rugby fields, 381 of those fields had not been physically impacted by trawling for decades. The trawls were about 1/10th as long as a commercial trawl which may impact 1–10 km2 (MacDiarmid 2012). This is largely due to the horrific sediment plumes they create, especially on mud which most of the trawls in restricted areas were. This means the total trawl distance of 53.35km could have impacted up to 40km2 (6,349 rugby fields) of seafloor – choking animals and smothering plants.

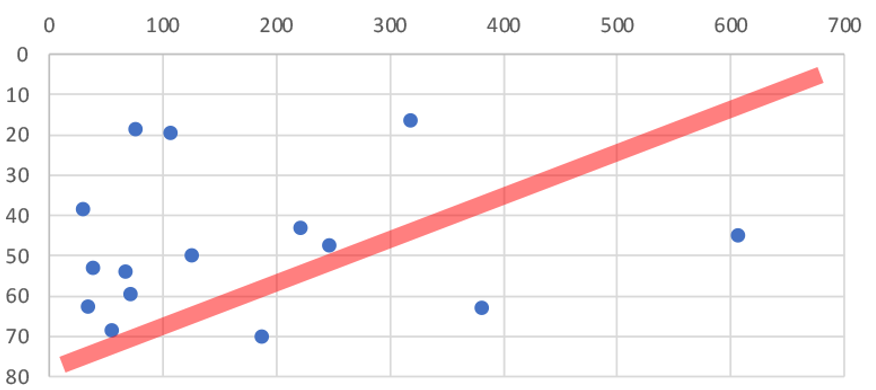

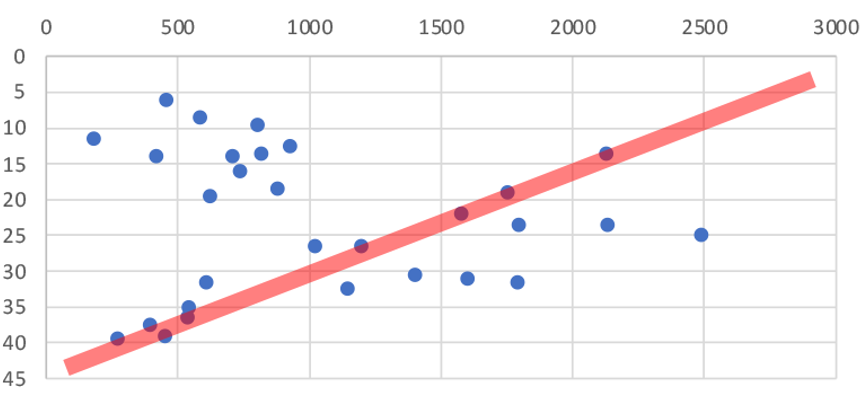

The average catch weight per trawling station in restricted areas was 500% higher than areas where bottom trawling is not restricted (1,033kgs vs only 171kgs). That’s a huge difference, the commercial fishers pulling up the nets must have been blown away with the haul! There was no significant difference in the size of the trawls but there was a big difference in depth. Trawls in trawling restricted areas averaged about half the depth (23m) of those in regularly trawled areas (47m). So are the fish benefiting more from trawling restrictions or depth?

As you can see from Figure 1 & 2 there is no correlation between depth and catch weight (red line vs data). There could be many other factors involved (FNZ seemed to deliberately avoid trawling on sand in the inner Gulf so we can not directly compare substrates), but the 500% increase in catch weight in areas protected from trawling shows that protecting the seafloor from bottom trawling dramatically increases the amount of fish that live on the seafloor.

The survey is good news for recreational fishers who shouldn’t leave the inner Gulf to catch more Tāmure / Snapper. If you’re a fisher who wants to know where demersal fish are in the Gulf I recommend you read the report (NZFAR 2021). If you want to know which trawling station got the highest catch… I’m not telling! You will have to ask FNZ, you can send them an OIA request Official.InformationAct@mpi.govt.nz why don’t you tell them to stay out of the restricted areas and stop bottom impact fishing at the same time 😀

The total weight of fish (mostly Tāmure / Snapper) landed was 41,759 kilograms! 80% of the dead fish was sold for $128,449.35 which seems like a lot but with Tāmure at $20-$30 per kg at the supermarket they could have made more than one million dollars selling it direct to consumers. Of the total revenue from the two years of survey approximately 73% ($93,634.47) was absorbed in operation costs of the research vessel to process the catch. The remaining balance ($34,814.88) was returned to the Ministry of Primary Industry. That means even selling the dead fish dirt cheap the surveys make a profit for the Government. The self issued scientific permit to trawl in restricted areas is more profitable than some whaling trips the Japanese government justifies as science.

I was surprised to see invasive species like Mediterranean fanworm (Sabella spallanzanii) turning up in the catch. They are very skinny and should fly through the nets. There must have been very dense beds in places. It was disappointing to hear from my Official Information Act request that Biosecurity New Zealand was not informed of which stations had high numbers of the Unwanted Organism. The lack of interagency communication (even with MPI) sucks but the double standard is worse. When restoring the seafloor from fishing damage the Mussel Reef Restoration Trust must notify an MPI technical officer if it accidentally releases an Unwanted Organism (a legal requirement of moving Unwanted Organisms under the Biosecurity Act 1993). Bottom trawlers however can move them around the Gulf with no regard to Biosecurity. This shows how Biosecurity NZ favours industry over community groups.

The surveys continue despite FNZ no longer having a public license to bottom trawl the HGMP. There is 84% public opposition to fishing methods that impact the seafloor (Hauraki Gulf Forum 2021). Most fisheries scientists take samples 100’s of times smaller or use baited underwater video cameras to count and measure fish. FNZ definitely don’t have a social license to trawl in restricted areas but they are ploughing on. Because I make a living doing science communication its not in my interests to criticise the research survey but I had to because I think what they are doing is wrong.

I included trawl stations in areas where Danish seining is allowed and trawling is restricted in the restricted totals. The three stations had an average catch weight that lowered the average restricted catch weight and increased the average catch depth.

Sea Change 2017. Sea Change – Tai Timu Tai Pari Marine Spatial Plan. Hauraki Gulf Forum, Ministry for Primary Industries, Department of Conservation, Waikato Regional Council, Auckland Council. 2017.

MacDiarmid 2012. Assessment of anthropogenic threats to New Zealand marine habitats. A. MacDiarmid. New Zealand Aquatic Environment and Biodiversity Report No. 93 2012

NZFAR 2021. New Zealand Fisheries Assessment Report 2021/08. Trawl surveys of the Hauraki Gulf and Bay of Plenty in 2019 and 2020 to estimate the abundance of juvenile snapper. 2021. https://fs.fish.govt.nz/Doc/24856/FAR-2021-08-Hauraki-Gulf-2019-Bay-Of-Plenty-2020-Trawl-Surveys-4125.pdf.ashx

Hauraki Gulf Forum 2021. Results of Hauraki Gulf Poll by Alex Rogers. The Gulf Journal

https://gulfjournal.org.nz/2021/11/results-of-hauraki-gulf-poll/ Accessed December 2021

NIWA 2019. NIWA to survey young snapper in Hauraki Gulf. https://niwa.co.nz/news/niwa-to-survey-young-snapper-in-hauraki-gulf Accessed December 2021.

I have illustrated most of the mobile animals you might see on a protected shallow reef in North Eastern New Zealand. It’s available as a canvas print, framed art print, metal print, photographic print and poster on Redbubble.com

If you buy one please send me a photo so I can see how it looks, below is the large poster in semi gloss. I was really pleased with the result and will stick it on the wall by my dive gear.

Here are a few closeups.

All my profits from the sale of the work will go toward marine protection initiatives in New Zealand.

I regularly get asked for several graphics from the State of Our Gulf 2020 so I am posting them here so everyone can access them.

Commercial bottom trawling and Danish seining. The Sea Change – Tai Timu Tai Pari Marine Spatial Plan 2016 (Sea Change) recommend these fishing methods be removed from the Gulf, this is inline with the Hauraki Gulf Forums (The Forum) goals. It is disappointing to see the Government push any decision to another committee, however they have suggested ‘most’ trawling will stop which is hopeful. Currently both practices impact about 77% of the Gulf.

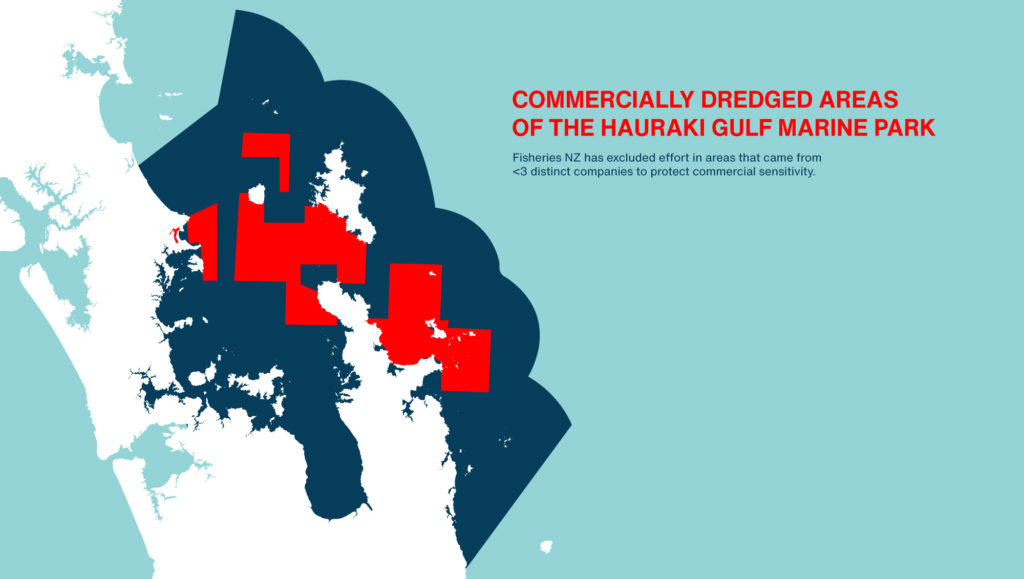

Commercial dredging. Sea Change and the Forum also recommend this destructive practice be removed from the Gulf. No changes here with huge heavy machines scraping ~37% of the seafloor. In 2016 current Minister of Oceans David Parker said “Fisheries New Zealand has been captured by industry” it seems that has not changed with Mr Parker now heading up the portfolio. I am hoping the areas are reduced in the Fisheries Management Plan as most of the effort (~300 tows PA) currently happens around the Mercury Island Group.

Recreational dredging. Stopping this is a huge win for the Gulf, it opens up the entire Inner Gulf for restoration and I think it should have been the headline. However I think its unlikely that recreational fishers will think this is fair given commercial dredges have much more impact on the seafloor. The Inner Gulf is much more degraded by bottom impact fishing than the Outer Gulf with over 122 years of scraping. It’s really exciting that from 2024 it can begin the long process of recovery.

Marine Protected Areas. No take marine reserves go from 0.33% to 0.575% of the Gulf. This is a significant increase, but a pathetic overall result. Experimental ‘High Protection Areas’ with customary take by permit will attempt to protect 6.2% of the Gulf. These areas will not come into effect until the end of 2024. I expect we will have to wait at least seven years before we know if they work.

Fisheries Management Plan. Also pushed to another committee. I am deeply concerned that the changes above will not arrest the decline of the Gulf especially with looming climate change impacts. The entire approach is relying heavily on the Fisheries Management Plan which they claim will be ecosystem based.

Existing ‘No Take’ Marine Protected Areas in the Gulf:

| Cape Rodney-Okakari Point Marine Reserve | 5.6km2 |

| Te Whanganui A Hei (Cathedral Cove) Marine Reserve | 8.8km2 |

| Long Bay-Okura Marine Reserve | 9.6km2 |

| Motu-Manawa-Pollen Island Marine Reserve | 5km2 |

| Te Matuku Marine Reserve | 6.9km2 |

| Tāwharanui Marine Reserve | 4km2 |

| TOTAL | 39.9km22 |

Sea Change ‘No Take’ extensions

| Whanganui-a-Hei (Cathedral Cove) Marine Reserve | +15 km2 |

| Cape Rodney-Okakari Point (Leigh) Marine Reserve | +14 km2 |

| TOTAL | 29km2 |

The Hauraki Gulf Marine Park is 12,000km2 or 14,000 km2 of ocean depending on what you read, I’m choosing the smaller number.

Sea Change brings ‘No Take’ Marine Protection in the Gulf from 40km2 to 69km2 or from 0.33% to 0.575%.

The other 11 proposed High Protection areas are experimental in that they allow customary take by permit. They could meet the protection level required to be designated as MPAs, depending on how mana whenua choose to undertake their customary practises. They are:

| Te Hauturu-o-Toi/Little Barrier Island | 195.4km2 |

| Slipper Island/Whakahau | 13.5km2 |

| Motukawao Group | 29.1km2 |

| Firth of Thames and Rotoroa Island | 12.4 km2 |

| Rangitoto Island and Motutapu Island | 10.7km2 |

| Cape Colville | 26.7 km2 |

| Mokohinau Islands | 118.5km2 |

| Aldermen Islands | 133.9 km2 |

| Aldermen Islands South | 155.0 km2 |

| Kawau Bay | 40.4 km2 |

| Tiritiri Matangi Island | 9.5 km2 |

| TOTAL | 745.1km2 |

Or 6.2% of the Gulf.

The technical analysis of the proposals has assumed that these areas will be ’No Take’ but Government has decided to use special legislation to progress the ‘High Protection Areas’ rather than the Marine Reserves Act, there is no indication as to why. The areas which will be enabled through new legislation which will not be passed until 2024, this means the process which started in 2013 when completed will have taken 11 years. As the areas include customary take by permit, they are experimental. I don’t know how long we will then have to wait until we know if the experiment works or not. I am deeply concerned it’s not even close to enough protection to restore functioning ecosystems in the Gulf. The existing reserves and extensions plus the High Protection Areas only add up to 6.775% of the Gulf (excluding any seafloor protection like cable zones). The Government is putting a lot of faith in a Fisheries Management Plan that does not yet exist.

Errors (as I find them):

Page 39. “Since then, large scallop and oyster beds have largely replaced mussel beds in areas of habitat degradation.” The areas are dominated by mud, invasive species are the dominant epifauna.

Page 39. “Significantly increasing the amount of freshwater” sentence is not finished or doesn’t make sense.

Page 107. Climate change resilience excluded from Draft Fisheries Management Plan. Incredible that in 2021 a Govt department can still make a plan that excludes known climate change impacts.

UPDATE 23 July: MAC report released

The Ministerial Advisory Committee was not impressed with the first draft of the action plan, and it looks like many changes were made. However it is hard to tell what was changed as (like the action plan itself) it is very short on detail. The biggest criticism seems to be on the timings which I really agree with, Govt is moving incredibly slowly given the urgency of the problem.

The other general criticism is around resourcing. This paragraph well articulates my frustration in reading the ‘active restoration’ section of the report.

“Our major concern with this part of the strategy is a complete lack of reference to funding sources for restoration. While identifying regulatory barriers is mentioned, there is no mention of funding barriers, which are arguably just as significant. Active restoration efforts will require resources to implement and sources of funding should be identified.”

I am very pleased to see that Govt listened to one member of the MAC that questioned blanket customary take in the MPAs. I hope many iwi will support no-take in HPAs because they will want them to have maximum mauri, and only no-take MPAs are known to work – anything else is an experiment.

A lot of the rest of the criticism is around governance. I am not interested in ownership of the Gulf or the power dynamics… just environmental outcomes.

UPDATE 30 July: OIA on dredging areas refused

OIA response here. I have emailed the officer to ask for the survey results and a follow up meeting.

UPDATE 6 August 2022:

I got no response, so sent in a new OIA request for the data and survey. I then got a phone call. They are 6-8 weeks away from publishing the NIWA HGMP scallop fishery survey results (so my request for those will be declined). Aggregated Electronic Catch and Position Reporting (ER/GPR) data would be available if I provided a specific time frame and area. The data could be provided visually E.g. a heat map. I have done this.

I was also informed that the conversation around management options for the scallop fisheries is internal, management options will not be made public but will be provided to the Minister in several months.

UPDATE 6 September 2022

I received a response to my OIA request (Heatmap A, Heatmap B). I have added the dredged areas together and removed the proposed HPA’s, SPA’s and CPZ’s to calculate the percent of the HGMP that will be ‘frozen’ under the Governments plan to ‘revitalise the Gulf‘. More than 20% of the Gulf will remain heavily impacted by commercial dredging with no public input into the decision.

Update 28 September 2022:

The cost to create $774.1km2 of Marine Protection Areas in the plan (assuming they are no-take) to 11 commercial fish species was calculated to be $3,436,014. If we crudely scale up the figure for the gains to snapper / tamure alone based on this paper we get $209,710,000. Or a net gain of more than 200 million dollars! This is an incredible number, MPAs would not be adding so much money to commercial fisheries if they did not manage fish levels at such incredibly low numbers. Clearly Fisheries New Zealand should be making MPAs (at speed) all around NZ.

Update 28 October 2022:

Our painfully detailed submission on the marine protection proposals.

Here is my submission on the proposed Waikato Regional Coastal Plan.

TL;DR Less mapping, more controlling the effects of fishing.

Second submission after further consultation.