Here is my submission on the proposed Waikato Regional Coastal Plan.

TL;DR Less mapping, more controlling the effects of fishing.

Second submission after further consultation.

Mostly just stuff I am doing to help the planet

Here is my submission on the proposed Waikato Regional Coastal Plan.

TL;DR Less mapping, more controlling the effects of fishing.

Second submission after further consultation.

I have begun doing some work with the Northern New Zealand Seabird Trust who invited me to come and help them with some field work on the Poor Knights Islands. My father had visited the Islands when he worked for DOC in the 1990’s, his stories about the reptile abundance really inspired me to do restoration work, and I jumped at the opportunity to go.

Landing on the Island is notoriously difficult and our first shot at it was delayed, we had to go back to Auckland to wait for better weather. The islands are surrounded by steep cliffs that made European habitation impractical, Māori left the area in the 1820’s. This means the island I visited has never had introduced mammals, not even kiore! I spent days cleaning my gear to get through the biosecurity requirements which are incredibly strict for good reason.

I have explored a few predator free islands including Hauturu / Little Barrier Island which has been described as New Zealand’s most intact ecosystem. However it was only cleared of rats in 2004. When I am photographing invertebrates at night in mainland sanctuaries or forests with predator control (like Tāwharanui Regional Park or parts of the Waitakere Ranges) I see one reptile every eight hours or so. On Hauturu / Little Barrier Island I see them every 20 minutes, but on the Poor Knights it was every two minutes! Bushbird numbers were lower than other islands, I expect this is because reptiles and birds compete over prey species. I wonder if reptile numbers on other islands might be slower to recover because they are preyed on by bushbirds. I reckon that the Poor Knights total reptile and bushbird biomass is much greater than the restored islands I have visited. One reason for this is that reptiles use less energy to hunt than bushbirds but the other reason might be because it has more seabirds.

While walking through the bush at night I would sometimes hear a crashing in the canopy followed by a soft thump on the ground. In an incredible navigational feat the seabirds somehow land only meters from their burrows. At night I heard Buller’s shearwater, grey-faced petrel, little penguins and diving petrel (fairy prion finish breeding in February). While monitoring birds at night I was showered with dirt by a Buller’s shearwater who was digging out a burrow. In my short time on the island I saw cave weta and three species of reptile using the burrows. Like a rock forest the burrows add another layer of habitat to the ecosystem. It was incredibly touching to see the care and compassion the researchers had for some of the chicks who were starving while waiting for their parents who often have to travel hundreds of kilometres to find enough food. The chicks who don’t make it die in their burrows and are eaten by many invertebrates, the invertebrates in turn become reptile or bushbird food. The soil on the island looked thick and rich, when it rains nutrients are bought down into the small but famous marine reserve which is teaming with life.

I was only on the island for three nights but I was very fortunate to experience a pristine ridge to reef ecosystem. Seabirds are incredible ecosystem engineers who were an integral part of New Zealand’s inland forests for millions of years. Communities are making small efforts to bring seabirds back to predator free island and mainland sites with no control over seabird food sources. If we really want intact ecosystems we will have to make sure our oceans have enough food for seabirds to feed our forests.

I really like this list of alternative words for environmental terms, offered by George Monbiot & Ralph Steadman. I have rebuilt it in HTML with some additions and deletions, I plan to evolve it over time.

| Existing terms | What’s wrong with it | Alternative terms |

| Environment | Cold, technical Seen as seperate | The natural world |

| Global warming | Warm sounds pleasant | Global overheating |

| Biodiversity | Inaccessible | Wildlife |

| Ecosystem services | Anthropocentric and reductive | Life support systems |

| Nature reserve | ‘reserve’ suggests coldness | Wildlife refuge |

| Habitat destruction Deforestation Biodiversity loss | Sounds like they are happening to themselves | Ecocide |

| Conservation | Preserving what little is left rather than rebuilding living systems (New Zealand needs a department of Restoration) | Restoration |

| Clean rivers / seas | Sounds too hygienic, is blind to waters as habitats | Thriving rivers / seas |

| Fossil fuels | Suggests redundancy | Dirty fuels |

| Sustainable development | Green growth is an oxymoron | Regenerative development |

| Photopollution | Too technical, doesn’t indicate what is being impacted | Ecological light pollution |

| Stormwater | Suggests that the water is unwanted, unnecessary or unsavoury | Rainwater |

| MARINE | ||

| Fish stocks | Suggests fish are here to serve us | Wild fish populations |

| Biofoul, foul, foul ground | Suggests there is something ugly about biogenic habitats | Sea life, seafloor life, benthic epifauna |

| Fishing | Casual everyday activity | Killing native wildlife |

| Bait fish | Implies the fish exist to be bait | Small schooling fish / forage fish / small pelagic fish / shoaling fish |

| Bait ball | Implies the fish exist to be bait | Tight ball of fish |

| Seaweeds | Pest connotations | Ocean plants |

| Mobile bottom contact fishing | Implies a light touch | (Mobile) Bottom impact fishing |

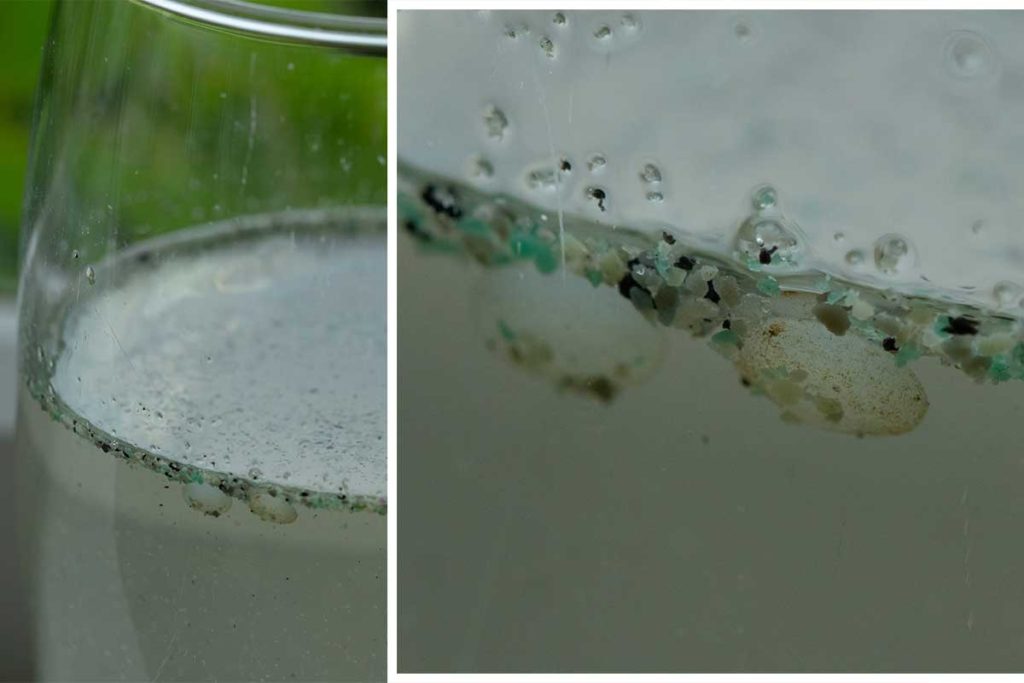

Bailey Tanks make their water storage tanks from plastic which comes into the business as small pellets. Since August 2017 I have seen these plastic pellets coming out of their business at 36 Ash Rd, Wiri and into the local stream where it flows into the Manuaku Harbour. I have been regularly reporting the pollution to Auckland Council who have been asking the business to clean up their act, they were fined $750 on the in May 2017 however the plastic keeps coming out.

Today (22 February 2020) I thought I would go and see if the rain would increase the amount of plastic washing to the stream. Pallets were coming but I was horrified to see the surface of the water covered in a fine plastic powder which they also use to make their products. Council job number 8260232660.

Industrial pollution is usually event based, where a business has accidentally spills something and creates a pollution incident. This kind of slow leak is much worse, I hate to think how much plastic this company has dumped into the Manukau Harbour where it poisons our wildlife.

UPDATE: 24 May 2020

UPDATE 13 OCTOBER 2020

The site was the cleanest I had ever seen, the business is clearly trying to clean up their act which is great. (Just one plastic pellet sighted). It’s a shame that they just cant stop leaking plastic tho. Check out the tiny bits of plastic powder in this video. Council RM Incident 8620239074, INR60239074.

UPDATE 25 FEBRUARY 2024

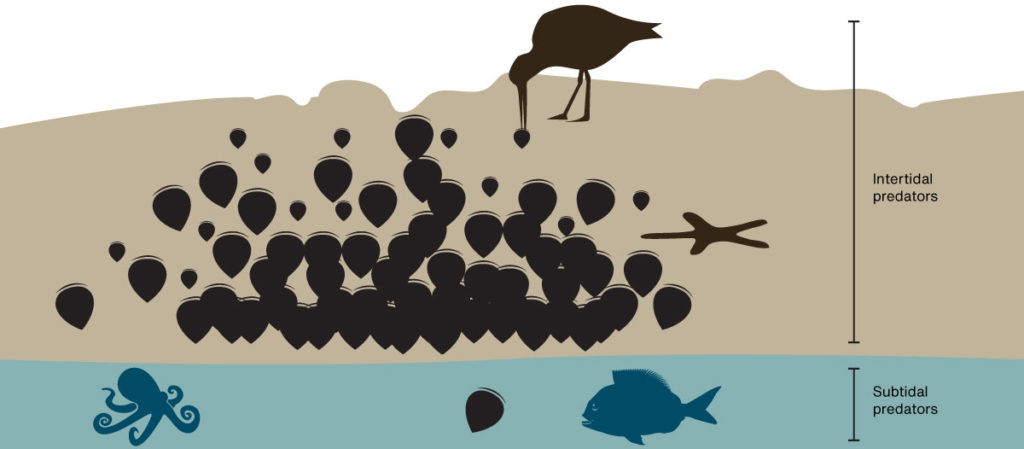

Marine restoration is a lazy business. All you have to do is stop fishing an area and marine ecosystems heal themselves. However this is not the case with green-lipped mussels in New Zealand.

100’s of square kilometres of sub-tidal mussel beds were fished to extinction in each harbour around New Zealand.

The industry collapsed and more than half a century later they have not returned. In the Hauraki Gulf there are a few places you can still find Green-lipped mussels. You would think that these places would be deep under the ocean (Green-lipped mussels have been found at 50m deep), but they are not.

Most are in the intertidal zone on rocky shores. Here there is usually a gradient with mussels thin higher up and getting thicker towards the low tide mark where the abruptly stop. I have asked several local experts and no one has a solid answer why they stop so abruptly.

As we spend 100’s of thousands of dollars restoring sub-tidal beds maybe the key to unlocking a lazier (and cheaper) solution is staring us in the face. Here are some thoughts on why the line exists:

Or maybe like a lot of things in biology it’s a mixture of the above factors. As we are slowly losing our intertidal mussel beds it might be wise to set up a long-term monitoring project that might solve this mystery and inspire lazier restoration methods.

I was recently lucky enough to monitor kiwi on Hauturu with the Little Barrier Island Supporters Trust. I have done this many times before at Tāwharanui with TOSSI. The exercise involves a good hike to the destination at night then sitting quietly in the dark listening to the sounds of the forest for a couple of hours. I have met some great people doing this and this trip was no exception. They patiently waited for me as I inched along the tracks on the way back to the hut, inspecting every tree for hidden treasures and some even came out with me again on their free nights. I have posted all my invertebrate observations here on iNaturalist where the community is helping me identify them all. I have also posted some fungi which were a hot topic among the volunteers.

It’s an incredible island where one can get a sense for pre-human New Zealand. Here is a list of some observations I made over the 12 days I was there.

The population of any given species needs to be strong enough to handle destructive natural and made made events. Without this resilience one event can wipe a species of the face of the planet forever. In New Zealand our rarest endemic breeding bird is the New Zealand fairy tern. With a population of only 40 birds this is the breakdown for the 2017-18 season.

It’s a fragile population with too many males (1:2 ratio). The other major concern is that during breeding season 80% of the population is on the same 40km stretch of coast. Here is where the breeding happened in 2017-18:

East coast:

Waipu 2

Mangawhai 5

Pakiri 1

West coast:

Papakanui 2

The fragility is particularly exposed when we think about the threat of an oil spill from the RMS Niagara. This wreck is a time bomb just off the coast from this critical breeding habitat. Even a small amount of the submerged oil could easily cover the fairy terns breeding grounds for weeks, starving the birds to death in a matter of days.

Book recommendation: This book by a NZ adventurer and herpetologist is awesome. It’s a refreshingly honest collection of great adventures and scientific discoveries. I throughly enjoyed Tony’s detailed descriptions of New Zealand’s treasures, his passion is inspirational. I really appreciated him sharing the highs & lows of what has been an outstanding career… so far. Get it here.

I made iNaturalists observation of the week. Read about leaf-veined slugs here.